Jivan Baba Chapter

We take up the tale of Jivan, whose travels with Babaji were of longer duration than those of Tularam and the longest that we know of.

We take up the tale of Jivan, whose travels with Babaji were of longer duration than those of Tularam and the longest that we know of.

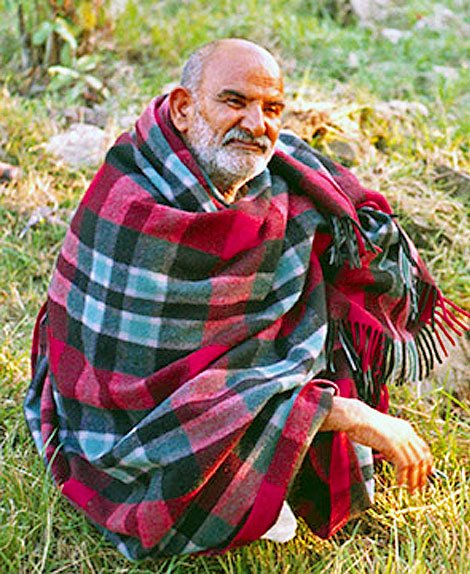

After his period of travel/companionship, he came to be known as Jivan Baba, a transformation and elevation that might have seemed unusual to Jivan's near and dear ones.

This transformation would not have seemed unusual to those who had seen many such cases before.

Those who saw or knew the murtis only, but not the craftsman, saw each as distinct and separate from each other. But for those who had met the craftsman from whose hands the murtis came, and had seen him at work, they were not distinct.

All the murtis were the products of the same master hand.

The unique underlying qualities could not be traced by judging one or two of them at random, but when you took them as a whole, you could find the missing link. The predominant thing was that every one was perfect and complete in itself. This remark does not refer to all and sundry who came to Baba for darshan, but only to those whom he had chosen for special treatment. Their number is small as far as we know.

There was not any major difference in nature between Tularam and Jivan when they came out of the master craftsman's workshop. They were first emptied of all unwarranted and spurious things, and then cleaned and purified. These processes were different for each, but when complete, each newly filled vessel was filled with the sacred water. The cases of Jivan or Tularam were not isolated ones. Taken with those of Bhabania, Brij Mohan, and such others, there was unity in their separation—the unity of the separate flowers in the same garland. The flowers were different, but the florist was the same for all of them.

Jivan belonged to an educated, middle-class family from the Nainital region. His education was dictated by the customs and traditions of his class and family. He had not taken special training or higher education that would have qualified him for a particular post, for he had made a decision at an early stage of life not to take any job. His father had died when he was young and he came to be entirely in the charge of his mother, which became the determining factor in the course of his life.

By nature, Jivan was gentle and soft-spoken, helpful, forgiving, generous and large-hearted. He gathered many friends and spent most of his time in their company. He was not possessive or aggressive, so his relations had no reason to restrain him and he was allowed to live as he wished. With his soft heart, he would become highly emotional when he started singing bhajans, often with tears in his eyes and a choked voice. Everyone enjoyed his golden voice and his friends often got together for a musical spree with Jivan in the center. To get their enjoyment in full, they took the aid of food and then crowned it by taking a few sips.

In the beginning, such gatherings were small, with restricted doses of drink. But from the modest start, they gathered momentum and grew very large, with eating and drinking taking the form of ritual. Soon, they were carried to many places in that region, where Jivan became popular. He and his friends believed in enjoying life. With no family responsibility and no need to earn money or support anyone, he could 'eat, drink, and be merry.' There was no transgression of public morality or indulgence in any obscenity, so there was no opposition. They ate their own food in their own homes, drank by spending their own money, and kept their smoking restricted to their own chosen places.

This was how Jivan lived in the early stage of his life. He was innocent and pure of heart and did not harbor any ill or evil to anyone. He had no sinful ideas in his mind and no unworthy acts to repent, so he was fearless and moved freely with his friends.

It was painful to his mother and near relations to see such a precious life going to waste. He had been born into a decent family, but instead of becoming the succor and shelter of his relations, he had actually become a burden for them. They worried about how to bring him back to the right track. However, they knew Jivan well and were convinced that this was not in their power; it would have to come from somewhere else.

Every mother wants well for her son, but with mothers like Jivan's, there were added responsibilities. The supreme task before this old, affectionate mother was to bring him into the pattern of family life that had been followed for generations. She was convinced that her son was good, honest, and pure, and that there was nothing wrong in his make-up; he had just taken the wrong path.

Jivan's mother was accused of being responsible for the course of life her son was living because all the money came from her. But she could not be hard or stingy with him. It was a case of the weak hand holding the string loosely. When the wind blows, the kite soars high and moves this way or that. The nature and make-up of the kite is to rise and move. When not checked or controlled, it is the fault of the hand that the kite is on the wrong side. This was no doubt true for Jivan's mother. But when her hands were weakened by love, how could she get a strong grip to control her son?

This was the root of her helplessness. She felt that the only path open to her was to pray to her Lord, her Ishtadev (personal god). She was a deeply religious lady who spent most of her time in prayer and worship, but whereas most ladies of her age and status prayed to be free of worries in the afterlife, her prayers were directed for her son's transformation. She was a great devotee of Babaji and he gave her darshan whenever he came to town. He knew what her problem was, so she had no need to apprise him of it. If she could only throw a halter made with her religious and spiritual fibers round Jivan's neck—the halter she had prepared through her life of prayer and pious living—she had full faith that Babaji would take it up. She had only to wait for the right time.

Babaji was an eyesore for Jivan; Babaji's very name was so repugnant to him that anybody who talked to him about Baba would only be inviting abuse. He quarrelled with his mother over her devotion to Baba and the fact that she entertained him in her house. He felt it was a crime for her to meet Baba but he could not deter her since Babaji always came in his absence. So his hateful vigilance was begun.

There was an interesting incident in the life of Ram Thakur. He and his devotees had come to Benares and were going over a narrow road when they saw persons running helter-skelter as if to save their lives. They were warned that a mad bull was rushing towards them and they must all run away. His devotees ran to different sides, but Ram Thakur did not budge. The bull was dashing towards him, people in adjoining houses were shouting at him, but to no effect. The rushing bull came and suddenly stopped before Ram Thakur, as if some spell had set to work. The bull bent his head and moved away in a slow and careless way. Gone were the rage and fury and the mad rush to charge. Everyone witnessing this was stunned. How could it happen? Who was the person who could tame a turbulent bull?

One day Jivan learned that Babaji had come to town. Now he only had to watch his house and wait for Babaji to visit his mother. A little higher dose of drink was needed to release him from useless debates of right or wrong and gather full strength and courage for his task. He must not falter or fail, but must finish his challenge for good.

Babaji arrived, and was walking down the road followed by many devotees. Jivan was waiting to march to his adversary, followed by some of his friends. Everyone saw him rushing madly toward Baba with a shoe in his hand. They all shouted and some tried to stop him, but Babaji prevented this by saying, "Let him come. He wants to face me. Allow him to do that for which he has waited so long." Jivan came face to face with Babaji, but collapsed at his feet before he could raise the shoe to strike. He could not look at Babaji and so missed seeing the bewitching smile and the glowing eyes, free from all traces of fear or fury. It was a smile celebrating the success of the venture for which the mother had been praying all her life. The halter had been caught up and the direction of Jivan's movement could be changed for the benefit of all.

People came rushing and gathered round while Babaji moved away slowly, unnoticed by anyone. His work was done. Jivan was crying—perhaps trying to empty his eyes by shedding the last drops. He was actually lifted and carried to his home. It was an occasion for jubilation—the triumph of his mother's patience, perseverance and undiluted affection for her son. Everyone believed that it was going to be very significant for Jivan—the turning point in his life. The miracle had been done. Only time would reveal how it would work itself out.

Jivan started his new career with an earnestness not seen before by his relations. He stopped going to the old gatherings, and sought in their place contact with Babaji's devotees. Babaji was well known in the Nainital region and almost everyone had experiences and stories to narrate. Jivan sought their company and spent all his time this way, intoxicated under the new spell. Another request of Jivan's mother, for which she pressed Babaji hard, was to get Jivan married. She did not live to see her wish fulfilled, but he married during Babaji's lifetime and lives with his wife and sons.

One day, a number of western devotees were standing before the window of Babaji's room at Kainchi. I was with them. He put a question to them through me, "Do you take drugs?"

"Yes, Baba."

"Why do you take drugs?"

"For intoxication. The miseries of life sometimes become so acute and intolerable that we run for all kinds of remedies to help us forget them."

"How long does your intoxication continue after one dose?"

"Just for two or three hours at a time."

"Why don't you repeat your doses for more?"

"It is very harmful, Baba. The effects on the stomach and the mind have to be kept under rigid control, therefore we cannot take more."

"So, this intoxication comes to an end quickly and damages the health and mind. This is not good."

"What can we do, Baba? We do it under compulsion knowing full well that the effects are going to be bad."

"Why do you not take God intoxication? It will never end, and you can spend all your time, your whole life in it. There will be no harm or damage to anything. Also, you will get back your lost health and vigor and your mind and heart will be fully restored. This is nectar, amrit. If you take this intoxication, you will be freed from all your illness and worries."

Jivan had experienced that in his own life. That night, when I narrated this dialogue to him, his response came in the shedding of profuse tears and half-uttered words, "He is all in all and everything comes from him."

Jivan's rise was rapid. He became an important figure in Baba's 'Night Brigade'—as it used to be called by the people of that area—moving all through the night, halting at any place without caring anything for shelter or food. Jivan never missed a march by sitting and resting and was always ready to help everyone with whatever they might need. Tularam valued Jivan's company most highly. While others could join the brigade life at night only, Jivan had no such problem. He had no job with routine hours or responsibilities to a family and was able to move anywhere at Babaji's beck and call. He soon had his chance to be with him when others were not near. He had a thin supple body, and being mentally free from all obsessions of high or low, fit or not, he did any work needed by Baba. It was a training in mobility and self-effacement.

One night, Baba had sent the others away after midnight. He and Jivan started walking. Babaji said he was having some pain in his knees and could not walk anymore, so Jivan should get a rickshaw for him. He sought for one but returned saying no rickshaw was available. Baba shouted, "Do you not have eyes? When so many rickshaws are there, you could not get one?" Babaji was right. The rickshaw pullers had deposited their rickshaws and gone home. Jivan had his eyes opened and could see. He went to the rickshaw stand, took one and pulled it himself. Babaji got on it and ordered him to move. How long they went on like this, he could not know, but the comments kept coming: "You know all the roads, lanes and by-lanes here. Pull the rickshaw very carefully—no jerks or sudden changes of direction. You are an expert in this job. Where did you learn it? It seems you have been a rickshaw puller all your life."

They were going by the road near a small cottage when Babaji asked him to stop. He said he was hungry and Jivan should get some food for him. Jivan knocked at the house and woke the people up, but their regret was that there was no food they could offer Babaji right then. They said they would have to prepare some and came to take Babaji to their home. Babaji said that he was very hungry and could not wait anymore—they must bring whatever was available; some chapatis and chutneys must be in the house. They were reluctant to give only that, but he started shouting, "You have no mercy for me. When I am so very hungry, you are not giving me food?"

They were helpless. They rushed back home and returned with the dry chapatis with some pieces of chutney. He started eating, fully relishing the food. It took no time at all to put them in the right state of mind after being forced to serve the food against all their expostulations. "You actually get the taste of food when you are hungry. Whatever you eat then becomes so sweet on your tongue."

They were feeding Baba, sitting before him. Jivan was given a couple of maize corns as there were not enough chapatis for him. He was sitting a little away from Baba and eating the corn, his food for the night. When Baba finished they were sent away and he asked Jivan what he was eating. He took a small piece of corn from Jivan's hand and tried working his few teeth on it. He told Jivan it was good and he relished it, thereby adding taste to Jivan's dry corn. He had many such experiences. Many 'certificates' were given to him when he tried his hand at various kinds of jobs. "You understand things so quickly and do your work efficiently." Jivan's remarks about this were: "Everyone was praised lavishly for whatever little you did for him."

When Jivan completed his preliminary training, he was drafted for long and hazardous journeys. Others only knew about that part of the journey in which they themselves participated as travel mate or companion and few were taken on more than a couple of journeys. Jivan was one of the rare few to our knowledge who served as Babaji's travel mate in many journeys over a long period of time.

Tularam's long journeys with Babaji were on the known and open roads, traveling by train or car. But Jivan's travel were in the interiors of the Kumoan and Garwhal hill, in places not reached by many and avoided by others. Here the journeys were through the vales and dales, across many streams and dense forests. The roads were narrow and steep, with wide detours. It was not all easy walking, but crawling and bending, climbing over sharp cliffs and going down hills while gathering momentum. On seeing them pass by, the cowherd boys would say it was 'the journey of the tall and the short.' When the road was broad enough, they moved side by side, one leaning on the shoulder of the other or catching his hand. The comment about them during this time was that they were 'thick and thin.'

Journeys through these areas were very slow with many hurdles, but Babaji and Jivan had no set time for reaching a certain place. Jivan said he never worried if the climb was steep or the journey risky. The strong hands would lift him, the firm grip would hold him against any slips, and the massive body, behind which he moved, was the armor which protected him from the calamities of life. Food was available in plenty—not only the fruits and roots of the forests, but also cooked food coming from the householders, sadhus and ashramites scattered everywhere.

Jivan had the same surprise while going with Babaji as did Ram Narayan Sinha on the streets of Mathura and Tularam on his way to the four sacred centers of pilgrimage: Babaji was known to everyone. Babaji was equally well known to householders and sadhus. His journey actually turned out to be moving from the familiar behind to the familiar ahead, everywhere being welcomed by all. Babaji was not fixed to any one place or tied to any person, however great or dear. He was free—no binding to hold him back, no attachment for anything—so he moved triumphantly.

Jivan was the silent spectator, his travel companion; all that was left for him to do was to move, fully enthralled. Living like this was so good—no drink or music could give this to you. As Jivan used to emphasize tirelessly, there was nothing missing and nothing left to worry about or deter you from your journey. All that you had to do was to move as the hands move when the legs are going ahead. If just for once you could disconnect your mind from your set notions and ideas, everything would be perfect.

One day they came to a beautiful valley, solitary and peaceful, with a narrow stream flowing nearby. They could sit there and relax, which they had not done for days. Babaji was sitting near the stream in silence. It was much afterwards when Babaji looked up and saw Jivan taking his bath in the stream, washing and massaging his body and then spreading out his dhoti in the sun. Babaji gave him the full chance to do that without any disturbance. It was only when Jivan was spreading his dhoti that Babaji said, "You are a very clever chap. You had such a nice bath in the clean water of the rushing stream. I will also take my bath. A bath in such pure water cleans your body, soothes your mind, and gives you fresh vigor and energy. You are very clever."

He threw off his blanket on the shore, entered the stream with his dhoti on and spent much time in the water taking dips and dallying. Coming out of the water, Babaji was sitting on the ground cross-legged with the blanket around his body. They sat there chatting while their dhotis dried. The stream had very pure water there, which you could not find in rivers on the plains, which were filled with all kinds of pollution. "God gives you everything pure and fresh, but greedy and selfish people turn it all into poison, and then they blame God for it. Can you understand it?" The reply Jivan gave was to sit silently and listen.

After some time Babaji started abusing him, "Do you want to spend the night here where there is no food or shelter nearby? The dhoti must be dry by now. I must wear it before I start. You may go in your langoti (loincloth), but I cannot go without my dhoti. I am not like you. When I am moving among people, I must be properly dressed." A good sermon to remember, at least for understanding his behavior when he was with the householders.

Walking some distance, they reached a small village with scattered cottages. They were welcomed by many of the villagers and decided to spend the night there. There were chapatis with potatoes and plenty of milk. Babaji took his habitual diet of plain chapatis with salt in such areas and left the vegetables and milk for Jivan. Early next morning they took to the road.

While passing through the outskirts of Almora at dark, several persons accosted Baba, pressing him to take his food that night in their houses. He refused everyone but ultimately yielded to one who followed him for a long time repeating his request, along with his complaint that Babaji had more or less deserted him, for what fault of his, he did not know. He said that Babaji had visited Almora several times during the last two years, but he had not been given any darshan. Babaji came to his house, sat on the verandah and talked to the people. The fellow started pleading with Baba that they should be given the privilege of serving him at night. Babaji readily agreed, saying that he would spend the night at their house.

The family had some difficulty believing this because they knew Babaji's peculiar knack for running away. The food was brought and much time was spent in the company of the householders, relishing their delicious food and praising them for knowing his taste. He said over and over what a good meal he had had. Jivan had already taken his food.

Babaji and Jivan were then taken to their room where the beds were laid. Water was kept for drinking with a bucket and a lota on the verandah. Babaji said, "There is nothing more that is needed. You are tired and must return to your room." When they pressed him to allow them to sit for some time with him, he sent them away, saying that he himself was sleepy and, pointing to Jivan, he said it would be a mercy if he was allowed to sleep now. When they left his room, they bolted the stair door from their side, thereby blocking the stairs for Babaji. They were suspicious and came several times to see that the door was not open. Babaji was sitting on his bed talking to Jivan, but stopped immediately when the footsteps were heard on the stairs. Finally they stopped coming for any further inspection, thinking it was already too late at night for him to run away.

When everyone down below was in deep sleep, Babaji pushed Jivan, abusing him, "You wretch. You want to spend your night here in sleep when someone is waiting for me outside. We must go now." He came out on the verandah, and told Jivan to take off his dhoti and hold one end tightly in his hand, hanging the other end down. Babaji caught hold of the hanging dhoti. Jivan had no difficulty in holding his end firmly because the person climbing down was not heavy enough to create any trouble for him. When he set his food on the ground, Babaji told Jivan to come down slowly. For mountain goats there isn't any difficulty in climbing up or gliding down and Jivan proved his mettle.

They had made some sound in their move, and the household people woke up. Coming to the door, they found it bolted, but reaching the verandah, they saw Babaji and Jivan down below. Feeling their eyes looking at him, Babaji told Jivan that they must run if they were not to be caught. The race started with each one trying to best the other. While running, they could hear shouting behind them, "Baba, so you ran away. We know that you deceive everyone, and we tried to stall you from running away, but you always find your ways of escape. We are helpless before you."

They covered a long distance and reached the outskirts of the city. It was the middle of the night and the whole town was asleep. They stopped before a small hut where an old woman was sitting in a room lit by a small kerosene lamp. Babaji tapped at the door. Opening it, she said she had been waiting for him with the chapatis she prepared in the evening and could not go to sleep without handing them over to him. He said that he had wanted to come earlier. He had been hungry and needed food, but had been imprisoned in a house where people were guarding him till late night. He was talking so much to convince her that it was not his indifference or negligence that kept him back. She was consoled and they left her to rest.

But there was no rest for them and they came to the crowded part of town. There was no one to watch them; all the doors were closed and people were asleep. Babaji sat down and asked Jivan to give him the food that was wrapped in his napkin—dry chapatis and potatoes. Taking them from his hand, he started eating. Jivan stood there silently watching. Babaji went on eating with such great relish as if it was the only thing he had to do. Jivan was thinking that only a few hours back he took so much delicious, well-cooked food as if he had not eaten for days.

When he had eaten most of his food, Babaji offered Jivan what was left—half a chapati and a few pieces of potato—telling him to eat it if he was feeling hungry. He said that he was not sure that Jivan would enjoy it as he had. One could enjoy one's food only when one was really hungry. "You have no hunger for such food, but I am always hungry for it." Jivan had nothing to say nor did Babaji want any reply from him, but it helped him a great deal to understand the whole drama that had been enacted that evening: how Babaji had been so very restless; how he had to run to a mother who was remembering him with such devotion and waiting with the food prepared by her own hands. Their journey ended for that time and they returned to Haldwani the next day.

Everyone who had accompanied Baba on his journeys enjoyed them in his own way, the differences being due not only to their tastes and preferences or their nearness and association with Baba, but also, as these devotees used to say, according to what Babaji wanted them to enjoy. Each one felt that their own experiences were true. This was actually Babaji's trick. He revealed to each one what he wanted them to see or enjoy according to their own interest or capacity. The old devotees sitting together in their satsangs agreed that each of their experiences were true and valuable for all.

Jivan's experiences were unique. Many of them were in striking contrast to others, and his observations are very illuminating in their own way. He preferred to move with Babaji in the hills and mountains, but he was not very enthusiastic while visiting the towns or urban areas. He used to say that when he was traveling with Babaji by train he had to restrain his talk so there should not be any indication of Babaji's identity; he had to behave, more or less, like a stranger to Babaji. For Jivan it was a strict discipline.

Visiting the urban devotees and sitting in their drawing rooms while Babaji was meeting people were not to Jivan's liking. He would stay away or sit in a corner as a disinterested spectator. It was so very different from what he experienced when he and Babaji visited the hills and the hamlets of the simpler, rural devotees. What a striking difference there was in the way Babaji talked and entertained his devotees in the two distinct places. Jivan's opinion was that Babaji was freer while he was in the huts, hearing the people's petty household difficulties. His reactions were immediate and spontaneous, with words of cheer and courage: their work must be done, responsibilities discharged, and they must remain satisfied with what was coming to them, never losing faith in God. It was very homely advice, but what joy and consolation for the humble seekers. Jivan used to say that you could get the real taste of Babaji when you were traveling with him in the mountains, through wayside villages and meeting stray travelers.

In the city there were busy people, well off in every way. Their interests were not in the big problems of society—the political, economic and what not. Their talks were often to acquaint Baba with their political and economic achievements and to seek his approval for their service to society. Sometimes they sought his advice on tricky problems facing them. He would hear everyone, ask them questions to show his interest in their problems, and advise them. He had a way of making them happy by responding to their requests and satisfying their curiousity in appropriate ways. No one felt neglected or disappointed.

One winter, Babaji was at Allahabad and we were enjoying our time with him. One day he decided to leave for Patna. As usual, nobody knew about his departure in advance. This was easy for him as no preparations were made for his journey. We were standing before him as he was leaving when he looked at Jivan and asked him to accompany him. Jivan was taken by surprise and only had a couple of minutes to get ready. Having traveled with Babaji many times before, he knew what was to be taken with him—only a change of clothes. When he came out with his small bag, we were admiring his luck, but Jivan was actually not very enthusiastic. Some of us noticed this and could not understand what was working in his mind. We found out only after he returned from Patna with Babaji and narrated his experience to us.

Four days passed, and we were all expecting their return at any time. On the fifth morning, I had a telegram from Patna, "Going by Delhi Express." It was so cryptic that everybody felt that Babaji was proceeding to Delhi and not coming here. All we could do was to meet him at the station. We were getting ready for the station, when Kanti and Ramesh came to accompany us. Kanti brought her tiffin carrier with food for Babaji's journey. Didi, on her part, was not lagging behind, already waiting with her own tiffin carrier. We were all ready to start. Looking at the ladies with their food for his journey, the idea suddenly came to my mind that Babaji might use this to foil my attempts of getting him to break his journey and stay here, so I asked the ladies not to accompany us. Ramesh and I would go to the station alone. I explained to them what was workng in my mind and trying to console them, I said, "Together, uncle and nephew have a lot of strength. If you would stay at home, we will bring him back." They agreed, and we left for the station.

When we reached the station, the train was already there. We rushed to locate his compartment and found him sitting there alone. Jivan was not there. He began all his usual inquiries, "Did you get my telegram? What did you do then? What did the people say when they learned that I was going to Delhi and not getting down here?" When I did not reply to his queries, he told me that he had some important work in Delhi and should be allowed to proceed—he would return after finishing his work.

Failing to get any response from me, he asked Ramesh, who narrated how everybody was disheartened that he was going to Delhi and how Kanti and Didi prepared food for him and were ready to come. "Then what happened, why did they not come?" Ramesh replied that I persuaded them not to accompany us, saying that there was enough strength with nephew and uncle. This came at the moment when the train whistled and was about to start. He actually jumped up in the train. "Yes, yes. There is enough strength. Let me get down."

I caught hold of his hand and Ramesh collected Jivan's bag. When we got down, Jivan came running. He had been searching for us all over the platform, but failing to see us, he was convinced that there was no chance of getting down and that he would have to board the train again. When he reached us, the train had already started. We four walked slowly together across the platform. Babaji was talking all the time, but it was difficult to know if anyone was hearing him. We were just trying to understand in our own minds how we had gotten him down from his scheduled journey so quickly when we had more or less lost all hope of it.

Coming out of the station, we took two rickshaws—Jivan and Ramesh in one and we two in the other. We started talking about the person whom Babaji had gone to see, a great devotee. He said that the devotee was ill and remembering him much, so he had to go. Then suddenly he said that I had done a very great thing. I could not understand what he was referring to. Then as if to help me to understand he said, "The dog was not yours, nor had she eaten the chickens, but to save her from them you gave the money to the young men."

I kept quiet. It had happened at the house two days back when I was sitting with Mathur on the verandah. The gate suddenly opened and a roadside dog came running very panicky, followed by some young men with hockey sticks in their hands. They wanted to kill the dog, alleging that she had eaten their chickens. However much I argued that the dog could not have done that, they did not agree and were talking only of their loss in so many rupees. I handed them the money and they went away, leaving the dog. Babaji was referring to this. It had happened when he was in Patna and was unknown to everyone in the house here.

When we reached the house, it was late in the afternoon and everybody was very excited by seeing him with us. He said he had been booked for Delhi but had to get down under pressure from these persons, pointing to Ramesh and myself. The whole house got busy with their work. Babaji had his bath, which he had not taken for three days, and was his usual self, taking his food with Ma, Maushi Ma and Siddhi Didi sitting around him. He said he was given food for the journey while leaving Patna but he had not eaten that, as he wanted to eat at home. This was his unique way of dealing with the mothers, whose highest joy was in feeding him with food cooked by their own hand.

All of us were anxious to hear from Jivan about his journey. At night, when Babaji had retired to his room, we got our chance and he gave all the details and his own relections.

They had traveled in a first class compartment where there were a few other passengers. Babaji was talking all the way of commonplace things so as not to excite interest or curiosity in anybody sitting there. They reached Patna in the evening. The devotee was a big landlord, well known in the place, and there were many family members and several servants. All of them wanted to serve Baba. Baba said for them first to give him tea and then to feed him, as he was hungry and hand not taken his food on the train. They got busy with Baba; Jivan went to the room meant for him. After his meal, Baba was sitting with the members of the family, who were all busy with their household affairs. When Jivan came to see him, Babaji inquired if he had eaten and if his bed was ready. After all the inquiries, Babaji told him to go to sleep.

While talking about it, Jivan said, "But how could I sleep? The whole thing, from coming to the station and boarding the train, to the journey to this place, had been a very tame affair, as if two unknown persons meeting at the station were traveling together." He was thinking of his journeys with Babaji in the mountains and of their thrilling experiences. Sitting in his lonely room and recalling them, he felt that this was lifeless, as if it was a punishment for him.

For the next three days, life was very busy with visiting many devotees in their houses and talking to the countless persons coming to Babaji. Hearing everyone and giving suitable replies was more or less a routine affair for him. Jivan was only a spectator, as there was nothing for him to do. While sitting in a corner of the drawing room of their host, the idea came to his mind that although there was nothing in the talks to interest him, there was a lot to see. The way Babaji was treating his audience with his retorts, gestures and the movement of his eyes, sometimes interlaced with remarks about some events or personalitites, threw everybody into peals of laughter which resounded in the whole area. One had to admire the acting, which changed with each stage and audience.

Jivan was excited while narrating this. Recalling some past experience, he said that no doubt there was laughter in the drawing rooms that he visited with Baba, but in the houses of devotees in the mountains and countrysides, he had seen how Baba could bring tears to the eyes by his remarks and gestures. "You become one with everyone and cannot resist your own tears. There can be no question of his acting. The idea cannot come in your mind. You feel in the very core of your heart that this is the Baba you want to be with. So you can understand why I want to avoid his drawing room visits."

Jivan had to stop there. He was choked with tears and could not talk. It was much afterwards that he could resume his narration, adding a few words about the return. "Many persons had come to the station to see Babaji off. Our seats had been reserved and we had comfortable berths. They brought some food for us for the journey. Pointing to the food, Babaji asked me to eat. There were chapatis, vegetables, and squash especially prepared for Baba. When I tried to serve him the food, he asked me to eat, saying he would take food only after reaching home. I was not very hungry, and the food was not to my taste. There was no salt in the squash and I did not eat it. Babaji asked me why I was not eating. When I told him there was no salt in the vegetable, he laughed and then said rather slowly, 'It is not easy to cook food. You have to give your full attention to it, only then will it turn out well.'

"There was no one else in the compartment so Babaji could talk. It was all about the people and how they loved him. He said that he was not like myself who could not mix with people and enjoy their company. Living in society and moving from one place to another, one must learn to mix with others—adjust to changing conditions and persons, not being too much involved in anything. Babaji said that he knew how to behave with everyone and be happy everywhere—not like me, sitting sulky, complaining and grumbling."

Once when we were talking about our experiences, Jivan said that it was futile to claim that you knew Babaji or could pass any judgment about him. He was always different from one person to another, one place to another, and different even at the same place but in different times. He said that everyone saw Baba in different ways, but that did not mean that anyone was wrong in his judgment. He himself had seen only a facet of him and not the whole, so how could he challenge anyone else because they had seen another facet? All of them were right. Moreover, we do not decide what we should see. The decision is always Babaji's; we see only what he wants us to see.

His other observation was also very striking. It was that Babaji was always acting when he was with you. He said that Babaji very seldom revealed himself, so that no one truly knew him. In support of this opinion, Jivan would muster up all of his experiences over the years, of sitting or journeying with him, in the plains and mountains, in the company of many others, or with him alone. He said in the same way we change our clothes when we go on a journey, visit a temple, or meet some celebrities, Babaji also changes. But whereas we only change our outward covering and make no change within, Babaji changes within as well as outside.

Traveling with Babaji in the hills, one noticed the way he moved, talked, shouted, and laughed. It was as if he had discovered himself anew. Gone were the acting and constraints that were expected of him. Rather, he could be himself as he really is. It was like the release of a block that was restraining the passage of water in a spring. Suddenly the water rushes out. So also were Babaji's movements, going anywhere and everywhere, talking and fraternising with everyone passing by, and showering his love and affection to those who recognized him from his previous visits. It was life—happy and cheerful for everyone to participate in and share. This was the reward that Jivan could never expect from anyone else, or even from Babaji in any other place. It could come only in the open, rough, rugged ground of the steep hills and forests.

Jivan was trying to explain why he was so keen to go with Babaji to the mountains while trying to avoid visiting the houses of his rich devotees in the towns. Jivan was firm in this judgment and could rightly be so, because of his extensive journeys with Babaji and also because of the deep devotion and intense faith he had earned through the ordeal of his apprenticeship. Talking about Babaji, Jivan would cry sometimes, but would always end by saying, "He is all in all."

Jivan said if we suffer for anything while going with Babaji, it is only due to our lack of faith in him. If we could rely on him and put ourselves entirely in his charge, things would be so easy for us. We feel ourselves to be so important, so we accuse him of failing us when we suffer. He said we all did it—even the so-called old devotees who claimed nearness to Babaji, as well as the new ones. Talking about this, Jivan would often get much excited and the story would break. I had to try to keep it going on while listening patiently.

Jivan had many more journeys with Babaji to his credit, and he would talk about them whenever we were sitting together. This practice which had started three decades back continues, giving us even more joy and relish now that we miss Babaji's physical presence.

Jivan was in Haldwani remembering Baba, whom he had not known for more than three months at that time. He felt he should go in search of him and that he might meet him at Bareilly, where Babaji often visited. Entertaining these ideas, he had just stepped out of the door of his house when he heard a friend calling to him, "Jivan, are you coming to Bareilly with me? You have nothing to do here now, so come with me." Jivan thought this must be a call from Babaji, bringing him out of the house and providing him with transport. The person taking him to Bareilly was his old friend, Yogesh, son of Shri Hriday Narain, a great devotee of Baba's from Bareilly.

When he reached the house of Dr. Bhandari, where Baba always visited when he was in Bareilly, he was told, "Jivan, you've come so late. Babaji was waiting for you here for so long, inquiring about you. Seeing that you were not coming, he left only a few minutes back." Jivan was convinced that he was not mistaken in coming to Bareilly. Babaji was actually calling him. When he said that he would go in search of Baba, the doctor said, "Where will you find him? He has so many places to go, and who could know where he would be at this particular moment?" But Jivan was not deterred. After visiting one house on the way, he came to the house of his friend, Hema Pandey and found Babaji there, surrounded by some devotees and members of the family.

Jivan took a seat in a corner, not presenting himself before Babaji. Looking at him, Babaji said, "Jivan, you are so late—I was waiting for you at Dr. Bhandari's house. Did he tell you I was waiting for you? How did you come to know that I was here?" Jivan gave no reply. These were not really questions, but Babaji's way of greeting his devotees.

It was noon and everyone had their meal after Babaji had taken his food. He went to his room, and spent a few hours meeting and talking to the people who came to visit him. Someone in the house wanted to close the door so that he could rest, but Babaji wanted to keep the door open, allowing those who wanted to, to see him. This was not a new thing for him. Whenever Babaji visited his devotees and spent time in their houses, he would see that nobody was refused his darshan. He would say that when people came to him, leaving their work or their rest, how could he not meet them? Those of his devotees who had been with him in his ashrams or in the houses of other devotees when Babaji was there, knew this well.

One day while staying at Allahabad, many visitors had come throughout the day keen to have his darshan. Babaji had returned after several days visit to Puri and Calcutta. At night, the mothers were waiting in his room with his food. He was reminded several times that the food was ready, but he never responded. When he finally came, he sat for some time, telling them that he was so very tired. He said, "One gets tired when meeting many persons, and also loses peace of mind." Ma said that that was his own doing, since he would not obey when someone wanted him to stay in his room instead of going out to meet people. Talking like a person who felt guilty of some disobedience, he said, "Ma, what can I do? I feel very unhappy if I fail to see people coming to meet me."

In this same connection one is reminded of the experience of Siddhi Didi and others when they were traveling with him in early 1973. At Bombay, they were taken to an ashram in Ganeshpuri. Babaji stayed back in his car while the others were sent for darshan. They returned after some lapse of time. When Babaji asked them about their talks with the Swamiji, they said they could not meet him—he had his own time for giving darshan and it was not yet that time, so they went away. After a few days, they came to Bangalore. Babaji sent them to visit a well-known saint in that area. They were not interested in the visit and resisted as much as possible, but he insisted and sent them to the ashram. He accompanied them in their car for some distance and then got down on the way and made them continue, saying he would wait for them there. After they returned he asked about their experience. The reply was that the saint had fixed hours when persons came to see him. So again they came away without having darshan.

Babaji exclaimed, "Did you see, did you see? Every saint has his fixed time for meeting people and sticks to that, but for me there cannot be any rule. However much I may fix my time, you and your Dada would not allow me to keep it. You will always force me out to give darshan although it is not my time." But how well we knew that there was no one—neither Siddhi Didi, nor myself, nor anyone else—who could make him do anything which he himself did not want to do.

The major part of Babaji's life was spent as a tramp, a baharupiya (someone who is capable of changing his form), as a sadhu who had known him for long had said. Even the closed doors of the ashrams or houses of his devotees were no barrier to his escape. The tramp in him would always beckon, making him run away.

In June 1971, in Kainchi, about three in the afternoon, he was in his room resting after his food. He suddenly came out the room without his blanket, wearing only a t-shirt. Everyone was taken by surprised by his presence at that unscheduled time and in such an unusual way. Although there was no fixed routine or time schedule for him, during the last few years of his stay in the ashram he used to retire for his bath and food at eleven in the morning and come out again at four, when he would meet everyone who had come. This was the practice to which people had become accustomed. Of course, he would sometimes come out to meet someone, but seldom without the blanket on him.

I was standing outside with many others. He caught hold of my hand and said, "Let's go." People were left gazing at him. We crossed the bridge and came out on the road. Seeing him coming, many persons gathered and wanted to touch his feet, but by a gesture of his hand, he sent them away. He was silent and when we had gone some distance, he asked me, as if only for my hearing, "Dada, have you been to Badrinath?" Hearing me reply that I had not been there, he said, "We shall hire a taxi for 600 rupees and visit there. You will return after that, but I will remain there. I love those places—the land of the gods! All the gods and the rishis live there. I shall also live with them." He stopped talking and was quiet as if reflecting on how life was to be there. Then as if awakened, he looked at me and said repeatedly, "You must not talk about it to anyone. No one, no one, must know of it."

This gives us some idea of the inner working of his mind and his real nature—a free spirit, ever free, allowing himself to be enclosed in the ashrams or houses of his devotees only out of his sheer grace for us. After Babaji had taken his samadhi, Deoria Baba talked about him to his devotees on several occasions. He said, "He is free, a realized soul. How could he remain bound?" Then he said that Babaji's devotees had raised an enclosure around him, thinking he could be held in that way. "How could this be possible? He might have stayed here for some time more had there been no such enclosure."

There came to be some truth in what Babaji had said about his being pushed out to give darshan to the devotees. This came to be prophetic for what was to happen in the last few weeks of his stay at Kainchi.

When he returned to Kainchi in 1973 after the Holi celebrations, the old routine of his coming out of his room at 8 o'clock in the morning, retiring at 11 o'clock and then coming out for meeting everyone at 4 o'clock began again. However, in a few days it was seen that Babaji had become so aloof from the ashram life and its routine that he could not follow it anymore. The changes that were taking place in him were not known to those staying at the ashram nor to the devotees coming for his darshan. They would assemble in the morning and afternoon as before, but would have to wait. It was so unusual for the old devotees that many would remark that he must not be well. "Did he not know we were waiting for him? How could this happen?"

Baba had lost interest in everything; it was only with great effort that he was making the body and the senses work. It would be long past eight o'clock in the morning or late in the afternoon and the visitors who had assembled would be waiting anxiously outside for him. Inside his room, Baba had no interest in the persons around and no knowledge of time or the work that was awaiting him. He just wanted to remain wherever he was, on the bed, on the chair inside, or on the toilet. He had to be reminded many times before he would come out. Siddhi Didi and myself, who were there with him, would have to make great efforts to bring him outside. Because of this experience over several months, we could testify to the truth of his statement that he was 'pushed out by us.' But when it came to the climax, then all the pushes and pulls failed to work. Nothing could make him come out of his room to give darshan.

June 15th was the foundation day of that ashram and the biggest celebration of the year. Preparations had gone on for days, with devotees from faraway places visiting for the auspicious occasion. The bhandara had been going on from early in the morning, with the malpua—the special prasad for that occasion—being given to everyone to eat and also to take home as a token of their visit to Hanumanji's temple.

As usual, Babaji had taken every care to see that enough had been prepared with all attention to its quality and purity. But unlike other years, he was not vigilant about the feeding and distribution of prasad. Formerly, he had stayed out of his room for the whole day, taking a few rounds across the ashram premises to see for himself how things were being done and to keep the workers alert. There was none of that this time. With great effort and persuasion, he was brought out in the morning, but he returned to his room without waiting for long.

By the middle of the day, thousands of devotees had assembled before the temple for darshan and streams of people were coming unabated. The greatest event of the day was to be the Ramdhun—Shri Ram Jai Ram Jai Jai Ram—played by Ram Singh with his police band, but they could not begin because Babaji was not there to grace the occasion. He asked me, as many others did, to bring Babaji out of his room. Little did they know that all efforts, all persuasions and even tears had already been ineffective.

After waiting for a long time, the band started playing, but everybody was looking toward the door to Babaji's room, hoping he would come out. I entered the room for my last attempt, but had to remain within until the music was over. I had found Babaji clapping his hands, singing Ram Ram, and moving around the room dancing. His dhoti was falling off and he was not conscious of anything around him. I forgot to do that for which I had come. Instead, I caught hold of his dhoti. I don't know for how long this continued, but it ended when the band stopped playing. Some mothers had come into the room and were standing as silent spectators to this unusual experience. Babaji might not be in the ashram for days at a time, but he would always return on this day to fulfill the expectations of his devotees and bless them by sitting with them. After some time passed, he came out for a short while. Many had already left, but many more were still there, not having given up hope of having his darshan. Nobody could imagine that it was going to be the last darshan of Baba, in his physical presence, on the annual festival day.

To return to Jivan's story, Babaji left Hema Pande's house with Jivan and visited a couple of other houses before reaching the station. He asked Jivan to purchase two first class tickets for Kotdwara. They would be going to the mountains to visit Kedarnath and Badrinath. Standing before the booking office, he was looking towards the road as if there was no hurry for him to get the tickets. Jivan was thinking that the money in his pocket was just enough for the tickets, but then nothing would be left for the rest of the journey. He also wondered if a blanket could be procured from somewhere, as the mountains would be cold at that time.

A few minutes passed, and thinking it was useless to wait anymore, he moved toward the counter. When he was taking out his money, he heard someone shouting, "Jivan, don't purchase the ticket. I am coming." Looking back, he saw it was his friend, Yogesh, with whom he traveled that morning. After Yogesh purchased the tickets they returned to the platform where Babaji was sitting. Jivan noticed that Yogesh had a new blanket on his shoulder. Was it an accident, sheer coincidence or the working of an unseen hand? These questions were in his mind, when he heard Babaji yelling at him, "You wretched, stingy fellow. You had gone to purchase the tickets, but without purchasing them you were looking toward the road to see if somebody would come and purchase them for you and save your money. Not only that, but you also wanted someone to bring a blanket for you. Greedy rogue, always looking to others to give you things. Now you should be satisfied with your tickets, the blanket and your money still intact in your pocket."

When the train came, they boarded it for the long journey to the hills and the forests, with no bags of clothes or food or anything else to carry. Just two pilgrims going empty-handed, each with only a blanket. For one, the blanket was for hiding, and for the other it was for protection from the mountain cold.

There were several others in the compartment, so there was not much opportunity to talk except for a few routine questions or answers. Jivan said that at least this once, so far as he could remember, he welcomed the silence. His mind was full, recalling and reflecting on the whole episode—coming out of the house in the morning in Haldwani, getting into the car with Yogesh for one journey, and now boarding a train in the evening, not with Yogesh but with Babaji. He saw it just like moving slides on a fixed screen. The screen (referring to his own mind) had to keep itself free for the slides to play. That was why he said he preferred to remain silent: so the slides could run.

While narrating the story he got excited and asked me several times how this could happen, although he believed that it was all Babaji's doing. "He is the one who does everything." His voice got choked, and he had to stop.

While waiting for him to resume his talks, I started recalling my own predicament when faced with a situation like Jivan's. Without waiting for him to begin again, I began to narrate my own experience, which often haunted me with all kinds of doubts, so he could clarify them for me.

In the beginning of May, Didi and I used to go to Kainchi for our uninterrupted stay of three months. Babaji had left Allahabad after Holi, and we were looking forward to our visit to Kainchi. During this time, Didi's mother had arrived, and Didi could not leave the house for too long as there was no certainty about the duration of her mother's stay here. The university was closed, and although I was free, I was persuaded not to leave for Kainchi without Didi. I had to wait, which of course, was not much to my liking. I spent three or four days trying to argue with them.

While this was going on, I felt very strongly one day that Babaji was remembering me and was waiting for my arrival. The feeling became so strong that I decided to leave by myself for Kainchi that evening. When I told them of my decision, they again asked me to postpone the journey for a couple of days more. Mashima said that if I went away, Didi would not be able to go alone. Then my mother produced her last card and said, "Babaji has asked you to stay at home. Since then, whenever you have gone out it was either with Babaji himself or when he sent his intimation. This time there is neither Babaji to take you along with him, nor any intimation from him. It would not be proper for you to go now."

Their arguments were strong, but stronger was my decision to start for Kainchi that very evening. All I could tell them was that I had my intimation. It was a case of transmission and reception, and I had received it.

Leaving the house was not easy. There was a tussle in my mind whether to yield to the pressure and stay at home, or to follow the call that had come without any further delay. These thoughts haunted me all through the night in the train, taking the sleep away from my eyes. Was I mistaken? Was Babaji actually remembering me? How could I believe it was so when there was no tangible proof to support it? The sense of guilt was also uppermost in my mind. Had I not disobeyed Babaji in leaving the house without his permission? Was it not a make-believe sort of thing to support my own desire to enjoy the life in the ashram? This was the state of my mind until I got into the taxi in Haldwani at noon. At that point, I could only look ahead to when I would meet him. Would he be annoyed that I had come, not obeying the mothers, forgetting what he had asked me to do only a half-dozen years back? I was trying to seek courage by thinking that nothing was unknown to him—he would know what had made me leave the house. There was no doubt that I had disobeyed the mothers, but I had not disobeyed him.

I was lost in this mental duel when the driver stopped in front of the temple at Bhumiadhar. He was booked for Kainchi, but he had seen Babaji sitting with a few others in front of the temple and he felt that we had reached the end of my journey. Seeing me approach, Babaji said that he had been remembering me for the last few days, as it was time for my visit. He asked, "Why was I late? Was the university closed? Why had Kamala not come with me? How were Ma and Mashima?" and other such questions which needed no reply. They were just his way of drawing me in. Then he asked rather excitedly, "Did you get my telegram? Did you get my telegram? When did you get it? I had been asking the people here to send you a telegram, but no one would obey me."

Unconsciously, without any thinking on my part, the reply came out, "Yes, I had the telegram." This was not a lie, nor a slip on my part, because in fact the telegram had been delivered to the house in Allahabad after I had left for the station. Babaji sent me inside the house to take my tea and eat something, after which we would go to Kainchi in the taxi that was waiting there. While waiting for the tea, Siddhi Didi said that Babaji had been remembering me, saying that it was time for me to come. "Because of the delay, he sent the telegram. He was sitting inside talking to us when he suddenly went out, just five minutes before your arrival, saying, "Dada is coming."

One gets thoroughly baffled when one tries to unravel the mystery. While I was narrating my story, Jivan was all attention, so addressing him I said "Jivanda, here are the replies to your queries, so far as I could understand them. The telegram proved that Babaji was actually remembering me and wanted me to come, which was my intimation when I was feeling agitated and wanted to go to him. Secondly, and more important, it demonstrated to my mother, Didi, and everyone else in the house that I was correct when I said that I had his intimation. Also, this was proof that I had not disobeyed Baba by leaving the house without permission."

It had its effects, not only in allaying Jivan's doubts and curiosity, but also in strengthening my own belief that you could not mistake his message when he remembered you. We agreed that when you receive his message, you should do as he wants you to do, without using your mind or brain, or seeking advice from others. The messages come even now, although Babaji is not in his body, but we fail to benefit by them. Our faith has lost its glory and flickers like a small candle before the wind.

These talks disturbed Jivan again. Tears came to his eyes, and his voice was choked. I was only to wait in patience, giving him time to recover. But it was not useless waiting. I was thinking how precious were these sittings of the devotees in what is called 'satsang.' It helps to remove the gnawing doubts in your mind, thereby increasing and strengthening devotion.

Jivan was able to resume his story. The journey took a long time to complete, and was spread over a wide area in Uttarkhand, including Kedarnath and Badrinath. From Bareilly to Pauri, and again while returning from Kedarnath, everyone else in the party was left behind and Jivan traveled alone with Baba. He was not so much interested in the beauty of the places they were going through, or visiting the temples or ashrams; he only wanted to hear and observe Babaji, and hear his talks with the village folk. Babaji had spent much time visiting all the areas of the region and would sometimes recall the persons who had met him there in earlier times. He said he had spent much time there visiting all the areas of the region. Many of those who used to feed him were not there. It was a long time back but there must be someone still alive. "The people used to love me and feed me well."

"One day while going by the side of an unnamed stream, Babaji said that the water was very pure and refreshing there. 'You can see for yourself that there are springs or streams all over the area and there are all kinds of fruits and roots in the forests. The sadhus who live in these areas, the mahatmas, do not have to worry about their food and drink. They can eat or drink when they need to. Moreover, those sadhus who do not stay in any ashram or temple and do not cook their own food sometimes get it from the people of nearby areas bringing it for them. You can see for yourself what I am saying. It is you people, the ever-greedy ones, who are always dying for your food—I must have it now, this variety or that, more or something for the next day. Most of your time and activities are occupied with cooking and eating. When do you have time for other things, for God? Food has become your god and goddess and all you want is food, more food—sweet, pungent and delicious.

"I have never bothered for food, but I have never been starving or hungry. It is the people who have bothered me with their food. Sometimes it has been a problem of how to keep them away with their food or how to keep them from bringing any more in the future. A sadhu should never worry about his needs or gather things for tomorrow. If one attempts to stockpile whatever is offered to him, that becomes his undoing. While staying somewhere, when people started bringing food for me everyday, I used to run away. I am not like you people, always looking for someone to give something to you—to entertain you with this or that.

"You choose your friends from among those from whom you can extract something. When you get your food, you forget everyone else. You do not look at others because of the fear that you might have to give a part of it. This is not my concoction. I have seen for myself, I have taken the test of many persons. I have visited many people in their houses when they were busy preparing their food. Some of them would leave their food and get busy for feeding me, but not everyone that I visited would be like that. There would be others who would be stricken with terror. 'What will happen, how has he come at this time? My food will be gone.' I can read this on their faces. Sometimes someone would ask me to eat when I was visiting them in their houses at mealtime, and I would eat. But never did I eat at the houses of those for whom it was painful to part with food or feed others. You may think I am exaggerating or unnecessarily accusing somebody, but what do you know of this? If somebody offers you food, you jump for it. I am not like you. I know that the food served by a miser or given grudgingly can never be digested. I would never touch it."

Jivan continued, "He was talking as if for his own hearing, not for advising me, but he knew that traveling in an unknown place with little money in my pocket, without any friends and relations from whom to seek help, there must be some fear lurking in my mind. He spoke like that to force my attention to that state of mind and to teach me that one should not fear for hunger or starvation when Baba was with him. Did it also mean that we must learn to rely only on him and not make any vain attempt to seek help from others?"

I had no reply to give to Jivan's question. I was thinking in my own mind that I saw many such things for myself, but learned little from them. If we are honest with ourselves, we have to admit that we have failed to benefit from his advice. Babaji is always busy teaching us, improving the 'pattern of our lives,' and making our lives more fruitful and free from worries. Can we accuse him of being indifferent to us and doing precious little for our well-being? Whenever a few of us have gathered together, we have often asked each other whether there have been any visible effects on any of his devotees from his long period of teaching. How far had Babaji succeeded in illuminating the minds of his devotees and molding their modes of life? Did he know what was to be the outcome of his long and strenuous effort? These questions agitate the mind. There cannot be any ready and uniform answers applicable to all the devotees who have been with him. We know that only he has got the answers, and we must not hazard any of our own.

Jivan said that there was no problem with food and shelter during their journey, nor was there much use for the money that was in his pocket. Badrinath had changed; with all its amenities and affluence, it had become a tourist center. The devotees who wanted nothing but to concentrate on Badrivishal (the deity of the place) could not help being affected by the environment and the presence of all kinds of visitors. Jivan said that at Badrinath a large number of devotees had joined them. So along with the darshan of the deity, they also had a social gathering of the old and well-known devotees in his shelter.

The journey to Kedarnath was somewhat different, at least for Jivan. The journey was not smooth and easy—one had to strive and strain in order to reach there. So it was not haunted by all kinds of seekers and non-seekers. Moreover, there was something like an atmosphere of austerity and serenity as compared to Badrinath. One could feel in one's heart, as Jivan remarked, that you were in the territory of the Yogi lost in meditation.

I have never been to Kedarnath and Badrinath, so there was no question of agreeing or disagreeing with his observations. Jivan further said that this time their party was small, as many had stayed behind or returned home, and for most of the journey he was alone with Baba. Babaji was on his dandi, Jivan was moving with him, and others were trailing behind. Babaji was talking, but at many places the path would not allow them to move side by side, and therefore much of his talk remained indistinct and inaudible.

While passing by some wayside houses, he heard someone shout from a nearby area, "Lakshman, Lakshman, you are running away. Could you not recognize me?" Babaji bent over in the dandi and covered his face with the blanket. Looking around, Jivan noticed a very old woman shouting at him—not following anymore, as she could not keep pace. After they had moved some distance, Babaji removed the blanket from his head and said that the woman had recognized him, as he had feared. It was painful for him to move away without talking to her, but that could not be helped. He might have been trapped had he stayed to hear her, and many others would have swarmed seeing her talking to him. Recalling the days when he had lived in that area, Babaji said that she used to bring food to him regularly. Seeing her doing this, a few others followed. There came to be more food than he needed. Even if he had asked her not to do so, she would have argued that it was her good luck to feed a sadhu. This kind of care might be the undoing for those engaged in their sadhana. So what could he do? He had to run away to where he was unknown, and avoid renewing contact.

After completing the journeys of Kedarnath and a few other places, Jivan returned to Haldwani, leaving Babaji with the others in the party. Jivan was convinced that Babaji's love for Kedarnath was not only for the sanctity of the place, but also because it was associated with his sadhana. Babaji, like many saints, would not disclose anything about the preparatory period for his sainthood. Another of these great saints was Jesus. More than half his life on earth was spent in tapas, the so-called 'lost years' in the life of Jesus. The same unknowing is also there in the days of the great saint, Ram Thakur, about whose sadhana Babaji used to speak so eloquently. Ram Thakur's devotees succeeded only in collecting stray bits of information from talks with him.

Babaji's devotees were not very successful in this regard either. So when Jivan said that part of Babaji's sadhana was in Kedarnath, it confirmed what was merely a guess until that time. Tularam had learned from the head priest of Dwarka when he was there in 1962 that Babaji had spent part of his life in that area. Pointing to Baba, the priest told Tularam that the Baba with the blanket had been here all through the time of his knowledge. It is said that there was a Hanuman temple nearby installed by Babaji. In 1973, when Babaji was going through the western mountains along with his devotees, he pointed out a particular place in that forest, saying that the picture of him with the matted locks was taken there during his sadhana.

Another clue came from Sri S. N. Sang, the principal of Birla College at Nainital and a great devotee of Babaji. He was very dear to us, and we sought his company whenever he was in Kainchi or Allahabad. Once he came to Allahabad and spent four days with us. He narrated his first experience as a little school boy reading in a public school in the Punjab.

"The students used to have a camp for few weeks in the mountains every year. We were in our camp in the Simla hills, collecting some flowers or running after butterflies, when we saw a man in a blanket passing by. We took no notice of him as there were so many persons coming and going. After a few minutes, a cowherd from a village in that area came running down shouting, 'Such a great saint has passed by and you did not run after him!'

"The question that we hurled at him was why he himself had not followed the saint. He said he had gone to call Santia (his wife) and other people in the village. When the people started going up the hill, we joined them. After quite some distance, we all came back as there was no sign of the man in the blanket.

"The cowherd began to talk of his boyhood days, when he had known that man in the blanket as Talaya Baba (the baba who lives in a lake). The cowherd said that he and the other village boys used to bring their cows and goats for grazing. The used to carry their food with them for the noon, as they would not return before the evening. After reaching a nearby lake, they would tie their food in a cloth and hang it on the branches of a tree.

"A baba used to live in that lake (talao) and was known by the name of Talaya Baba. Whenever they came there, they would see him in the water. He was very kind, and everyone used to talk highly of him as a sadhu but he used to tease them a great deal. When they came for their meal at noon, they would see that he had taken away their bag from the tree and had distributed the whole of it to the people coming to him, or to the animals. Then he would feed them in plenty with all kinds of delicious food—pure halwa, laddoo, khir—they would never have imagined tasting so many sweets together. He would get the food by putting his hand on his head or from the lake in which he was sitting. He loved them much and used to talk to them when they were near him.

"This was long ago. They were just small boys then, but he remembered everything about Talaya Baba. One day when they came with their cattle, he was not there in the lake. They searched for him on every side but could not find him anymore. A very long time had passed since they had seen him, but he recognized him as he was going by this road."

Sang continued, "I was caught in a dilemma. The villager was emphatic that they had actually seen him living in the lake, but we did not believe him then. How could one live in the water? But I confess, at this late age, after seeing him with my own eyes and spending a part of my life in his presence, with no doubt to distract me from my faith, I believe he is the Talaya Baba who lived in the lake."

These are just a few chunks picked up of the broken vase. Strictly speaking, they are not useful or necessary at all for the devotees who had seen him or heard of him. We may collect all the chunks of the broken vase, but that would not make it a new one or be of any use to anyone.

Jivan had so many more adventures with Babaji to narrate. "One morning Babaji came to Haldwani. It did not take much time for us to gather round him. When we were sitting with him, he suddenly stood up and said that he had to go. This was a shock for many persons who had thought he would stay there at least for a couple of days. All their pleadings were to no avail. He had to go, as the task was very important and very urgent. He shouted at me to get a taxi immediately. People who had known him for so long knew that this was not unusual for him—leaving at any moment without bothering about anyone's approval—but this time the hurry and obduracy was something different.

"When I brought the taxi, he got into it and ordered the driver to start. Quite a few wanted to accompany him, but he allowed only me and one other to take our seats in the back. When the driver turned the taxi towards Almora, Babaji said, 'Not that way, turn to the right.' Nobody was asking any questions, nor was Babaji talking to anyone.

"When we reached Bhimtal, we went to the house of a devotee there. Babaji started inquiring about certain persons, the places where they lived and such routine questions. More than an hour had passed; gone was the feeling of foreboding and the excitement of being made to move so suddenly. When the host brought a glass of milk for Babaji, he did not drink it, but asked him to get tea for us, as we had had to leave Haldwani without it.

After our tea, we moved to the house of another devotee, a school teacher. The house was near a park in which there was a Siva temple. While talking to the people there about the Siva-Ling under the banyan tree, Babaji said, 'It is easier for devotees to offer their pujas and prayers without the closed doors of the temples and the harsh rules of the priests. The temples and priests must have their rules, but they should not be used to keep the people away and cause them to lose faith in God. This is all the more important for those temples where the common people—the poor and uneducated ones—come for their worship. They do not have any fixed time of day when they are free from their work to do their worship. God is very kind, very generous. He loves His devotees. He has His own rules also. He would not spare Himself from His own rules, but it is not so with His devotees. They will come to the temple when they feel it is their own. Their God is there waiting for them, and they will not stay away from Him.'

"It was difficult to understand, then, why Babaji was talking like that about a temple that was more or less deserted, where very few persons cared to visit or offer their prayers and worship, but the talks had their own effect. The whole environment was surcharged with a charm, with a scent, with a vibration emanating from the temple within the park, as if to intimate to us that there was something more to come. Seldom did Babaji talk in such a high pitch about the glory and grace of God. This was my first experience of something like this, and I was lost in reverie."

"Babaji pointed to the teacher sitting there with us and asked him to go to the dharmasala in the park and bring back the South Indian gentleman living there. Everyone was surprised, saying it was a deserted mud building with broken tiles that served as a shelter to the pigeons and snakes. No human being could live there. But when Babaji insisted that he must go and bring the old man before him, the teacher had to go. After a short while, the teacher returned alone. He said he had been surprised when he saw that the doors, which always remained open, were bolted from the inside. He knocked, and at last an old man opened the window and asked him why he had come there and what he wanted. After he relayed Babaji's request, the old man said that he did not know any Babaji, nor was he interested to know him. He closed the window and moved away inside the room, so the teacher had to return. Babaji said, 'It's all right, you sit down,' and started to talk of other things, as if the matter had ended for him.

"More than an hour had passed when the mother of our host told Baba that food was ready and that he should eat now. Babaji told her it was not yet time, and looking at us, said we should go and bring the man and his wife; they would come now. We reached there and started knocking at his door loudly. He came, almost infuriated, and inquired why we were disturbing them and what we wanted from them. We reminded him of what was said before, that we were sent by Babaji to take them to him. He thought for a minute and then came out, saying that they would accompany us to meet Babaji. He was a South Indian gentleman, over seventy, looking very sober and distressed while moving with us. He spoke English and asked no questions.

"When they came and stood before Babaji, he shouted at them, 'You are maligning God. What is this? Do you think that God abandons his devotees so easily?' Babaji did not stop. He was talking as if to let out the stream that was agitating him. Everyone was struck dumb, unable to move and stood staring at Babaji. The old couple started trembling, with tears rolling over their cheeks. The old man attempted to speak, but had to stop, the tongue was not helping him. Seats were offered to them. They sat there silently, more to catch their lost breath than to find the words to speak.