Last Days

After 1970 I saw how very restless Babaji had become, that he just wanted to go away. He said, "Dada, I shall not have any more temples. It is very easy to build a temple, but so very difficult to run it."

After 1970 I saw how very restless Babaji had become, that he just wanted to go away. He said, "Dada, I shall not have any more temples. It is very easy to build a temple, but so very difficult to run it."

Since I had met him he had been talking constantly of building new temples and dharmashalas here and there—at Jagganath Puri, Badrinath, Chitrakut, Benares, Gaya, Allahabad. Suddenly it all changed. Now he bagan saying, "Dada, what is attachment for a saint? I shall run away."

This he would repeat many times a day, but I was not to tell anyone. I knew that it was with very great effort that he was staying.

He quoted, "'The yogi who is always on the move and the water that is always moving, no sediment, no impurity can stick to them.' I used to move so much, I used to move so much...I shall move again, I shall move again." Siddhi Didi also suspected something and when I was at Kainchi we would compare notes every day. She would say, "Dada, what is going to happen?" We tried our utmost to guard him in every possible way, but we could not speak of it to anyone else. We knew that he had no attachment for the ashram or for anybody. He was there and we were with him, that was all. It was like a rented house: while we are there it is so very dear to us, but when we leave it, we do not look back. Now when he said he would go away, I thought he would just be leaving the ashram as he had left other places. I didn't suspect that he would leave his body. After he took his samadhi, Rajuda's mother, who was a very great devotee, accused me of knowing that Maharaj ji was going to take samadhi. She would not believe that I did not know.

In Kainchi one day he was in his room resting after taking his food when suddenly he came out with just a tee shirt and dhoti on, no blanket. He hurriedly caught hold of my hand, saying, "Let's go!" We went out of the ashram and down the road. He asked, "Dada, have you been to Badrinath?" I said no. "We shall hire a taxi for six hundred rupees and go to Kedarnath and Badrinath. That is the land of the gods, rishis and the great sages. I shall remain there, but you shall return."

When I came to Kainchi in May of 1972, Baba told me, "Dada, I am not coming anymore to Allahabad. I have been coming there continuously for the last fourteen years. If one comes much and stays much, attachment comes."

People from Allahabad who were sitting there were furious with me because I answered, "Then don't come."

One morning Maharaj ji was with the Mothers in his room after taking his bath. Something had been said and Siddhi Didi began to cry bitterly. Maharaj ji shouted for me and said, "Dada, you take your Didi from here, otherwise I will go away!" They had been talking and he had said, "Am I indebted to anybody? Have I any attachment for anybody? Do you think that I am bound and tied? I shall leave Siddhi also!" This he went on shouting.

He began to have little consciousness of his body or his surroundings. Formerly in the morning he would do his toilet, clean his mouth, take a little milk tea and some fried gram flour. After that he would be very anxious to come out of his room. The Mothers would be doing arti to him and he would not want to wait for them to finish. But in the latter days he was not interested or willing to come out; he would just sit, talking and joking with the Mothers. One day he was talking about Draupadi's plan to charter a plane to take Maharaj ji and the Mothers and some devotees to America. He said to me, "Believe me, the Mothers have already prepared their frocks!" They all laughed so much.

Now it would be eight-thirty in the morning and the people would be waiting outside the room on the verandah. With difficulty I would bring him out, as if he had to go through a routine of work. He would sit and talk, but he did not have the old interest and energy.

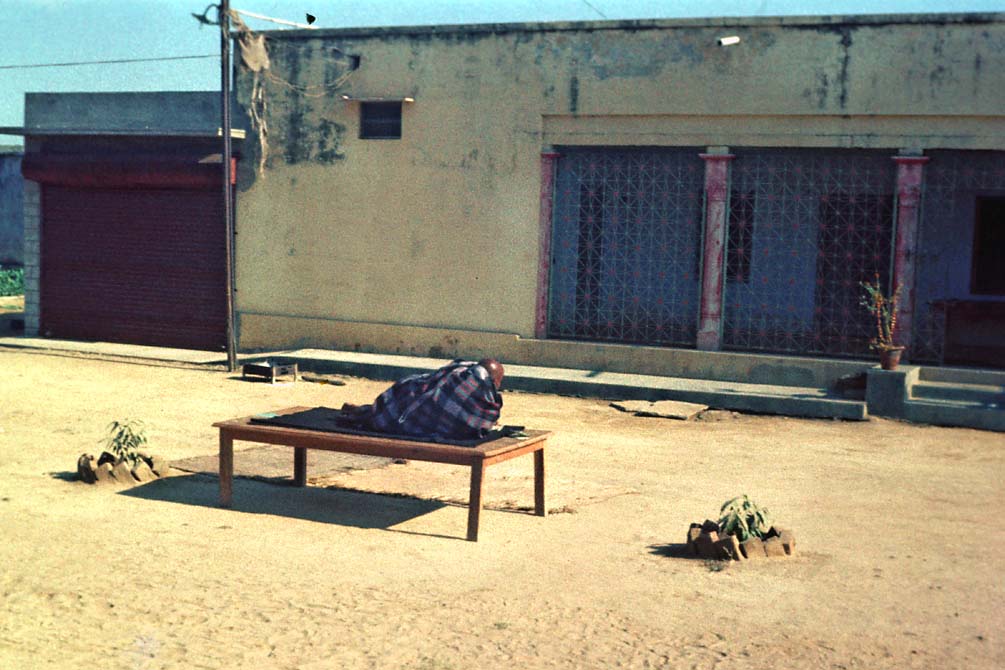

In the afternoon he would sit in the back of the ashram. Sometimes I would take him to urinate. Formerly, I would just wait nearby; now I had to sit along with him and catch hold of his blanket and his dhoti. One day I had gone to do some work and when I returned he jumped up and caught my hand and began running. Mr. Barman said, "Maharaj, as soon as Dada comes, you go away?"

Maharaj ji responded, "Dada forgets that I have to urinate."

One day coming from the latrine he dropped his dhoti completely. Siddhi Didi sent for a langoti and he came to the room and just lay on the bed to be dressed like a baby. He said, "Ma, I shall become a child again."

We would give him his food and he would just take the spoon and tap on the plate or move the food around. There was no question of eating. If we wanted him to eat, we had to take the spoon and put food in his mouth.

He also began asking for old devotees to be called, persons who had not been allowed to come to the ashram in many years. One of these was Thakur Jaidev Singh, who had met Babaji in 1934 but had not seen him since then. Even so, his love and devotion were so intense that when he was called, he came. Babaji was sitting before the showers and saw Thakur come through the inner gate. He was a very tall, old man and came with his son and grandson, who were holding him on either side. Babaji told me, "Go and help him."

But when I went and tried to catch hold of his arm, he said, "I have come to the person from whom all help comes. No other help is needed here."

At the June fifteenth bhandara in Kainchi in 1973 there was a record number of people. Everyone was asking me to bring Babaji out, but he sat in his room, unwilling to move. "No, Dada, let me rest, let me rest, I don't want to go." The ceremonies could not begin because he would not come out. After I tried twice and he would not come, the band began playing.

Later I went to try again to bring him and found him alone singing "Shri Ram, Jai Ram," dancing with his dhoti falling down. I had to catch hold of his dhoti and stand there. I had never seen him like that, with so little body consciousness. It was as if he had already left and only the body was there.

In 1972 and 1973 he began collecting many provisions for the Kainchi ashram—so many bags of wheat, so many bags of sugar. In 1973 seventeen truckloads of firewood were brought and lumbermen from Bhowali came to cut it. He would ask, "How much is left? Will it last until October? There will be much need for firewood then."

As it came to be, Maharaj ji took his samadhi in Vrindaban and therefore the cremation and ceremonies were done there. The mountain people had wanted his body brought to Kainchi, but when Pagal Baba said it must be done in Vrindaban, they left and decided to have their own bhandara. When I came on the third day, I learned of the quarrel. It was very painful to see that the cremation fire was still burning and already there was a quarrel between Vrindaban and Kainchi. The Kainchi bhandara was to be the day before the Vrindaban one and we went there. But because we did not want to create more of a split, we and the Mothers left Kainchi on the day of that bhandara and went to Vrindaban for the main ceremony. Although there was very little money at Kainchi, that bhandara came from what Maharaj ji had stored up. He knew all that was to happen.

For myself, it had been the thirteenth of August when we left Kainchi, a month before his samadhi. Didi's college had already opened, my university was opening soon. We came to see Maharaj ji in his room before we went. He said, "You are going? When will you come again?"

"Baba, whenever you want me to come, I shall come."

He only said, "Accha." Later Siddhi Didi said that after we had gone he kept saying, "Dada has gone away, Dada has gone away, but the work will go on. When I go away, the work will go on."

He made everything clear, but no one understood. Although there was deception, he was actually telling everything. On the day that he left Kainchi, he was asked, "Why must you go today?" His answer was, "I have got a date tomorrow." When they asked, "When shall we come?" he said, "Come on Tuesday." [On the following Tuesday, September 11, 1973, Maharaj ji left his body in Vrindaban. Devotees were contacted on that day to come for the cremation.]

Maharaj ji took his samadhi. When we think of it, we may feel that perhaps everything has ended. But in my heart of hearts I have never felt that it was the end. I felt it was just a storm that had come and torn away some branches and leaves here and there, but the garden continued.

Even during the last days in his body, it seems he was showing his grace and saving me from a lot of unhappy dramas that would have been very difficult for me to survive. After he took his samadhi in Vrindaban, mesages were sent by phone to those who had connections. Because we had no telephone, an express telegram was sent to us. The telegram arrived the next day after noon, when I was in the university. When I returned from the university, I took tea in my room. Then my mother said, "There is a telegram for you."

I came out and read the telegram, which was from Ravi Khanna: "Maharaj ji has taken his samadhi, come immediately." I could not believe it. I was very much upset. When Didi returned from her college, she also read it and it was difficult for her to believe. She went to the neighbor's house and telephoned to the Barmans in Delhi. Mrs. Barman said it was true and that Mr. Barman had gone to Vrindaban in the morning.

We informed other devotees in Allahabad and it was decided that we would leave by the first available train. The train was at eleven o'clock that night and Rajuda, Pantji, Mukund, Kutul, Didi and I all went on it. We reached Mathura the next day in late morning. On the way to Vrindaban we passed two buses returning to Nainital with devotees who had come from there.

When we reached Vrindaban it was the third day after the mahasamadhi and there was a large crowd. The fire was still smoldering. The first person who came to us was Vishwambar. He said, "Oh Dada, you are so very late. We were waiting for you until yesterday afternoon, but when you did not come we had to light the fire."

On hearing this, of course, tears came to my eyes. I saw those very ugly pictures that were being displayed: a photographer had taken so many of Maharaj ji's body and they were being sold. It was very shocking, but I thought, "Baba, you have been so very gracious and compassionate all through and even in the last moments you did not forget me. Had I been here, I should have been asked to put a fire stick in the funeral pyre. You have saved me from it."

Nobody understood my tears. They thought I was crying in sorrow at his parting. They said, "Dada, you should not cry." How could I explain?

The next person that spoke to me was Mr. Mehrotra. He said, "Dada, you did not tell us that Maharaj ji was a heart patient."

I actually lost my temper and shouted, "What are you talking about? What disease, what illness did he not have? From the hair on his head to his tonails, each part and cell of his body was full of disease. He had taken my illness, he had taken your illness, he had taken from all of us. That is why we are enjoying our good life—he has paid for it."

It was so striking that the place where he was cremated was in the ashram courtyard where a row of trees had been planted a year or so before. When those trees were being planted in a line from the front of the courtyard up to the dharmashala in the back, Baba told me, "Dada, leave a gap in the middle and don't plant any trees there." Then when I saw where the fire was smoldering, I knew that he had prepared the place and that people were unnecessarily fighting among themselves that he should be cremated somewhere else. He knew much in advance what drama, what trick he was to play, and prepared the stage. I was feeling helpless because the parting was certainly very painful. One could not get over the shock so very easily. However I might argue and console that he is not gone, still I was a human being and could not take it with such a stout heart, as I sometimes pretended to do. I was very much upset.

Before we were to leave the next day, it was decided that the ashes and flowers would be collected to be immersed in a number of places. Some would go to the Ganges in Hardwar, some to the sangam in Allahabad, and other places. The ashes for Allahabad were to be brought to our house and immersed by us. Mukund, Rajuda, and others brought the urn there and it was kept in Babaji's room.

Devotees from Delhi, Lucknow and other places had asked us to wait until Sunday, when they could come and join in the ceremony. So for three days the urn was kept in the room and every evening the Hanuman Chalisa was sung.

On Sunday the urn was to be taken for immersion. On Saturday night, when the kirtan was over, the flowers were being collected from his bed and the bed cover was to be removed. The idea came to me that his bed could not be empty, as if everything had ended. How could his bed be empty when he had said, "I am always here?"

The idea came that there should be a picture, and the one that was at hand was a picture of his feet that was taken by Balaram. After all, a guru's feet are the same thing as the guru himself, rather more precious than the guru's body. The photograph needed a frame, but it was eight o'clock at night so the question was how to get one. I asked my nephew Vibouti to go to the Civil Lines market and buy a frame. Everyone said, "No, it is eight o'clock at night, the shop will be closed." But I insisted that he go and try. The photographers knew me very well and they lived in the adjoining area; he could take my name and get it. Vibouti returned so very happy with the frame and I was also overjoyed. The framed photograph was put on Maharaj ji's bed.

The next day such a large number of persons came, not only from Allahabad, but elsewhere also. The urn was taken in a procession to the sangam. It was the middle of September and the flood waters of the Ganges had not yet fully subsided, so large barges were engaged to take us to a sand bar in the middle of the river. In one barge the priest, Triveni Prasad, along with Mukund, Rajuda, myself, Didi, Mr. Ojha, Pantji, and many others took the urn.

Ceremonies had to be performed and there was no question of my doing them because I knew nothing about it. Mukund did them. Then came the offering of the rice bowl and they said I was to do it. Generally, the eldest son does it; but a saint is not supposed to have a son and therefore the favorite disciple does it. At first I refused to do it, but they insisted and finally I had to get down into the water. The current of the river was so strong that some persons had to hold onto me while I recited the mantras and made the offering. I had been more or less in a trance or semiconscious state all this time, but at that point I woke up and tears came in my eyes. I thought, "You have filled both my hands with all I desired, all the sweet and good things, and look what I am offering to you."

Some days later Didi and I went to Kainchi for the bhandara that was to be held there on the day before the bhandara in Vrindaban. I said to Siddhi Didi that we had to go to Vrindaban for that bhandara, in order not to create more bad feelings. So we and the Mothers left Kainchi just after the bhandara started and took a taxi to get the train at Haldwani. We reached Vrindaban the next day and the bhandara was going on. It was a very busy day, full of activity, with no time to sit or talk or reflect.

Later in the day more Kainchi persons came—Inder, Jiban and others. They said that after we had left, some people came with constables wanting to capture the ashram. They had said Babaji had left the ashram without an heir and since it was full of precious metals and jewelry it should be taken into government custody, otherwise it would be looted. It was a big problem for the devotees. Shankar Dayal Sharma, a devotee of Babaji who held a high position in the government, had come to Vrindaband to the bhandaraand I told him of the difficulty. He said, "Let us go to Delhi and take care of the matter." We reached his house that night where he telephoned the Home Minister. The Governor of Uttar Pradesh was contacted and ultimately a trust was set up to be responsible for the ashram. The trust started functioning in 1975 and I was connected to that until I resigned in 1976.