Kainchi

After the Kainchi ashram was built, Babaji began spending the summer months there.

After the Kainchi ashram was built, Babaji began spending the summer months there.

In 1964, when some devotees were going there, I was asked to accompany them. I explained that I had to stay back because Babaji might visit at any time.

When the devotees got to Kainchi, Baba asked what my reply had been when invited to come to Kainchi. Then Babaji said, "Dada cannot leave his house because of my unscheduled visits. But those who are near to me do not bother about me."

In May 1966, we received a letter from Babaji, who was already in Kainchi, asking us to come as soon as the university closed. Didi and I reached there within a week. This was our first visit. Babaji was waiting for us in his room.

While sitting with him, a devotee brought a basket of various kinds of fruits from his garden. Babaji took out some of the fruits and showed me which I might eat and which I should avoid. After I had my tea and prasad, he took me around the ashram.

It took only a few days to get acquainted with the routine going on in the ashram. After getting up early in the morning (we did not know if Baba slept at night or not) and finishing his toilet, Babaji would take a little tea, which was actually more milk than tea.

At about eight o'clock he would come out and give darshan, either to groups or to people individually in his small room or visit this and that part of the ashram. After giving darshan and meeting people, Babaji would retire for his bath and food at around eleven o'clock.

After finishing a very modest meal, he would be just inside the room, seeing the Mothers or some of the ashramites. But if somebody came with some problem, or was remembering him, he would immediately rush out of the room, in spite of the protests of the Mothers. He would come because the call of the devotees was much more important than his personal comfort or rest. Then at about four o'clock in the afternoon, he would come out again for about four or five hours, until he retired to his room at about eight thirty or nine in the evening.

When he was visiting Bombay and South India, Baba sent some of the devotees who were accompanying him to an ashram near Bombay to have darshan of the head of that ashram. They returned saying there were fixed hours when darshan was given and they had arrived too soon. Many other visitors waited, but they had left. The same thing was repeated when they visited Bangalore. Babaji sent them to an ashram for darshan, and again they arrived before the fixed hours and left. Baba said to Siddhi Didi, "Look, every sadhu has fixed visiting hours when he gives darshan in his ashram. But you and Dada do not allow me to fix up any time. You always push me out to give darshan to the people at whatever time they arrive." She did not reply.

When we first arrived there was a big tent for a yagna that was being celebrated. Many priests were engaged in doing the puja, and the number of visitors was increasing daily. Bhandara was going on—everyone was fed or offered prasad to carry away with them. Everyone was happy, but there were some exceptions.

One day a few political leaders came after visiting some cities in the area. They were welcomed and offered prasad, but their reaction was hostile. Seeing so much ghee and other ingredients being used for havan and the large number of people being fed puris, some of them flared up and said to me, "There is such a food shortage in this country and so many are faced with famine. It is a sacrilege to waste so much food. How this can happen in this ashram is beyond our understanding."

Babaji was not there at the time. Later he asked me about the episode. He said, "These are the persons who have become the guardians of the people. They do not know where the food comes from. They do not take the name of God, offer any puja or perform havans. How will the rains come and produce food? They forget God and think everything depends on them. The whole defect lies there."

One day it was getting to be time for his food, but the devotees kept coming, one after another. Everyone was welcome. The Mothers came to me, "Dada, it is past eleven thirty. You must take Babaji inside now. It's time for his bath and food." But what could I do? He himself was allowing everyone to come, listening to each with patience and interest. "Dada, it is one o'clock." Siddhi Didi was standing on the other side of the door, beckoning me. I tried to lift Baba up by catching hold of his hand, but he would not budge. He only smiled and looked at me and kept on talking to the people, knowing full well how agitated we were becoming.

After one o'clock, I bolted one side of the door to the room, so that only one door was open. After those who were already in the room left, I bolted the door. I made him stand up and said, "These people are coming to you after taking their food. They are asking you all the same kinds of questions: about jobs or promotions or transfers, or their children's marriages or examinations, or their husband's drinking and wasting money, or their illnesses—all their worldly and domestic problems!"

I was thinking especially about one old woman who was sitting there and wouldn't move out. She was asking, "Baba, my daughter-in-law has got four daughters, now she must have a son!"

Maharaj ji replied, "Wherefrom shall I get this son?"

"Baba, your grace, your ashirbad, can get it."

I was very agitated and told him, "Baba, these people are thinking only of their tiny problems without caring at all about you, that you must also need to take a bath and have your food."

He caught hold of my hand, smiled at me, and said, "Dada, you should not be angry. This is the world, this is samsara [illusion]. Nobody comes to me for my own sake; everybody comes for their own problems."

However, here also there were exceptions. The head of the Goraknath sect came to Kainchi one morning. The Goraknaths are a very great sect of sadhus in India and its head was a very powerful and influential man. He came and sat in Babaji's room. Babaji said to me, "Dada, Mahant Digvijaynath is a great saint, touch his feet." I did that. When some other people came, he also told them to touch Mahant Digvijaynath's feet.

The third time Babaji said this, Mahant Digvijaynath stood up and said, "Baba, you who are the saint of saints is sitting before me, and you are making others touch my feet?"

We were sitting with Maharaj ji near the front of the ashram when a sadhu came walking in the gate. He had a big jata and a beard, was wearing rudhraksha beads and carrying a trident. As soon as he saw the man, Babaji jumped up and ran toward him. Babaji met the man, spoke to him for a minute or two, and then the man disappeared. He just disappeared! Usha Bahadur cried, "Who was that person?" Maharaj ji never said a word about it.

One night after the gate was closed and all the guests had retired, I was going around checking that things were all right. I was surprised to see a stranger come walking towards me from the back, the river side of the ashram. He said, "I need a lantern. Can you give me one?"

I said that of course I could and got it for him. Then I asked, "How did you get here this late at night?"

He said, "I was going by truck, but it broke down. Therefore I have come to get a lantern. Don't worry, I shall return the lamp. You can go on with your work."

The next morning Maharaj ji said to me, "You met Sombari Maharaj?" I said no, him I had not met. "The man who took the lantern from you last night, you didn't understand who he was?"

One night, the full moon was just coming up and the whole mountain was illuminated. Maharaj ji said, "Dada, this is Gargachala." Gargachala means the place where Garga lived. Garga, like Brighu and Vashishta, was a very great rishi. He used to live and do his tapasya on that mountain.

Knowing the rishis are immortal, I asked, "Baba, can we sometimes have a vision of him? Can one see him here?"

He said, "Of course, sometimes he can be seen."

Some time later we were sitting with Babaji in the front room and saw a light on the opposite hill, a great illumination. We were very much excited. Babaji asked, "What are you seeing? What are you seeing?"

We said, "Baba, look! There is so much light!"

"Only light? You cannot hear the bell?" We could not. He said, "Well, well, Garga, you have given them the vision to see, but now you must give them the power to hear." Then he just said, "Jao, jao, jao," and the matter ended there.

When I first went to Kainchi the construction of the main buildings was over, but there were few bathrooms and latrines. For his morning toilet, Babaji used to go into the fields, several furlongs away. Moti Ram and I would accompany him in the jeep. After finishing his toilet, Babaji would sometimes sit by river; then returning to the road he would sit on the parapet giving darshan.

One day while Baba was sitting on the parapet, Mr. Chavan, the Defense Minister of India, was returning from Ranikhet with a large number of army officials. He was riding by in his car, and when he saw Babaji, he came out and prostrated before him. "Baba, it has been six years since I last had your darshan. This has been a very difficult time for us—there was the trouble in China and then the war with Pakistan."

The army officials, including a general, were gathered around Baba. Babaji said, "India is the land of gods. Nobody can take it by war and conquest. But if politicians give away the land in political games, who can prevent that?" Pointing to the soldiers standing there, he continued, "These are the people who have fought for the country. I went to the war fronts in Kashmir and other places and saw for myself what a fine job they were doing." Prasad was brought from the ashram then Baba asked them to go.

Although people were getting darshan at all times, the mystery of it remained the same. We realised that getting his darshan depended entirely on him. If he did not want to give it, one would have to be disappointed.

Once we had gone to the train station with Babaji to see him off. The train was late and he sat on the open platform, away from the people. Someone came and told him that a minister of the central government and some members of parliament were here and requested his darshan. Babaji rebuked the messenger, saying they were big "badmash" and he would not meet them. Before the train came, he started walking along the platform, holding my hand. He passed several times in front of the group that had wanted his darshan, but they never saw him.

One day Babaji and I had gone out for a while. When we returned, we saw a number of police constables posted on the ashram premises. The District Magistrate said that Mr. Nanda, the Home Minister, was coming the next morning to meet Babaji. Baba said, "Mr. Nanda can come, but the police must go. This ashram cannot be turned into a prison."

The D.M. said the police could be withdrawn only by government order. Baba asked him to send a telegram to Mr. Nanda telling him not to come to the ashram, but the D.M. said it was not in his power to do that. Babaji had Haridas send the telegram and Mr. Nanda did not come.

A governor of the state tried several times to see Babaji, but did not succeed. He was not coming as a devotee, but in his official position. He ultimately realised why he had missed darshan, and eventually did get to see Babaji.

Another political leader came to see Babaji and while he sat there Baba said to me, "Dada, he is such a generous man, such a large-hearted man. I have never come across a person like this! He is almost like a god!" But after the man went away, Babaji said, "He wanted to fool me. I am fooling the whole world, and he came to fool me!"

In 1966 there was an All-India Vice Chancellors Conference in Nainital, to which Vice Chancellors from different universities in India and Nepal had come. Having heard about Maharaj ji, they all came to the Bhumiadhar temple on Sunday to see him. They sat in Babaji's room and he talked with them. Their whole attention was focused on asking Babaji about the nature of his sadhana, who his guru was, what tapasya he had done, and that sort of thing. They were questioning Baba for more than an hour, but he had a nice was of escaping—smiling and replying, but not disclosing anything.

After their darshan, Babaji told me to go and give them prasad. They accosted me and asked what kind of spiritual power or realisation Baba had attained. I said I did not know. They would not believe me and insisted I must know these things. But I told them I was not only ignorant, but completely indifferent. They asked me why I stayed so close to him. I said, "The reason is this: whenever I am with him, I get so much of peace and joy that I forget everything."

After these gentlemen left, Mr. Mehrotra and Jiban, who had been listening, said, "You have always escaped like an eel from our questions, but today you were well-caught."

I said, "Look here, what great fun it was. These highly-educated people heckled Baba for more than an hour, but they could not extract anything. When they asked me what the greatest thing was about Baba, I could not tell them. But to you I can say that he is the greatest bluffer! He has kept everybody in darkness about himself."

Why he did or did not give darshan is difficult to understand. Often he would go out of his way to wait for his devotees. Once he was lying by the roadside in Mussorie in order to give darshan to Mr. K.M. Munshi, the Governor of Uttar Pradesh, who was to pass that way. In 1942 he was sitting on the open platform at the Allahabad train station to give darshan to the retired General McKenna, who was to pass the station in a special army train. In 1971 he was at the Magh Mela ground, waiting for Ram Dass and his party who were visiting that place on their way to Vrindaban in search of Maharaj ji.

One day he came out of the ashram in Vrindaban and sat on the road, which was full of dust and cow dung. He said this would be a protection from the crowd—no one would sit there for fear of making their clothes dirty. He himself had no such fear. Once he sat on human excreta and soiled his blanket. I had to rush to the ashram to get a blanket and then make him change.

We often felt that he had no consciousness of his body and cared little for its comforts. He would give darshan anytime day or night. Even in the last few years when the stream of visitors increased, with few exceptions he would meet everyone. But some persons did not have darshan no matter how they tried. Several times I asked him to give darshan to some persons who were visiting and he would cut me short, "Dada, you do not understand. They do not come for my darshan, but to test me. They are not interested in me, but in the magic that I am supposed to perform."

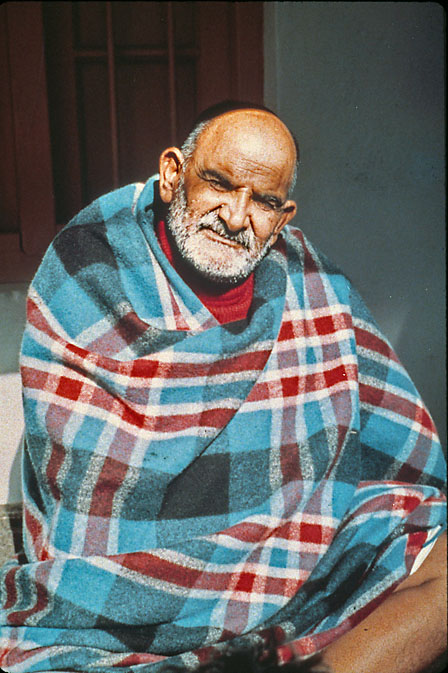

The saints choose different ways of doing their work. Babaji chose a life neither of a householder nor of a mendicant. He did not carry any of the outward signs that he was a sadhu or saint—no beads, no long beard, no saffron robes. No one could tell by looking at him that he was a saint. As we learned, even his name seemed to have changed from place to place. The name by which some knew him was Neem Karoli Baba (that is, the baba from Neem Karoli), but the correct words are 'nib karori' and perhaps give some indication of who that person was. Nib means foundation and karori means strong and firm: strong and firm foundation.

When Babaji first came to Nainital, Almora and other hill places, many of the menfolk were meeting him and he visited their houses. There the women, the Mothers, came to know him. But before there were temples and ashrams, there were few places where the women could be with him. He would not take them with him when he roamed about, nor had they the freedom or means to travel to see him. When the ashrams came to be built, these Mas would be coming in the morning and going away in the evening. These ladies were very religious-minded and they found Baba so sympathetic, kind and generous. He made it possible for them to spend so much time with him.

Maharaj ji was a father to his devotees, a guru of householders. His entire energy seemed to be directed toward our welfare, elevation, and development. He taught ideal social and family life, and showed us that real love and affection, real brotherhood, does not come only from blood relations. There were so many differences among the devotees—caste, language, nationality—usually very great barriers in India. But here were Kashmiris, Gujaratis, south Indians, north Indians, westerners—all part of his great family. He broke down the walls and removed the curtains of prejudice. In this family, we could be closer than with our real brothers and sisters.

He would say, "You have great regard and love for the Ganges and all the holy rivers, but you do not live on the bank of the Ganges. You live by a small stream: your house is there, you bathe and wash your clothing there, just as you would in the Ganges. But have this attitude: as the Ganges has come from him, so also has this stream come from him. It is the same water exactly; it is also holy. It will do the same thing."

Maharaj ji said that the family unit was the most important in society. He encouraged happy family life, love, brotherhood and affection. If each family became disciplined and followed the teachings of the elders and religion, life would be healthy and peaceful. But this could not be controlled and regulated by law.

He said that householders cannot be renunciates. If the householders would leave the home, leave the family and society, the country could not sustain them. The country needed the continuity of creation and work in the world. So he would tell us, "Feed the sadhus, give them money, give them blankets, whatever they need. They do not farm, they do not earn money, you must look after them. It is the householders' responsibility."

There were some politicians who thought that sadhus were parasites. There were so many lakhs of sadhus that had to be supported by society. They seemed to lead a prosperous life, although they did not work and earn. These politicians suggested that the sadhus be drafted to work in hospitals or schools. But Maharaj ji said, "What do sadhus know of such things? It would be their downfall. The politicians do not know the value of the sadhus and saints. Whatever their faults, they are keeping the lamp lighted, keeping the spirit living. As soon as the sadhus come in contact with money, with property, with business, that is their downfall. And their downfall is the ruination of the entire society."

Prabhudatt Brahmachari, that saint who has his ashrams in Allahabad and in Vrindaban, became rather well-known because he was leading the agitation about cow protection and clashed with the government. Maharaj ji told him that a sadhu should not become involved in political agitation. "A sadhu's work is bhajan and kirtan, puja and prayer. He should not go in for politics."

The great sadhu, Karpatri ji, led a religious movement for purification of temples and ashrams and the removal of Muslim mosques that had been constructed over the ruins of Hindu temples. He was also leading an agitation against the new law that permitted untouchables to enter the temples.

One day he came to Maharaj ji and said, "Such sacrilege is being done! You are a pillar of Hindu society. You must give your support and help us."

Maharaj ji was furious and told him, "In what way are you a sadhu? You do not go to the temple; you do not do your prayer and puja and bhajan. You are leading this agitation? I have seen some of the temples, there is no one to look after them. I have seen the dogs coming and urinating on the lingams! This is what you want to protect? Those people who want to do puja and prayer, you want to stop them? You do not go, but you want to prevent those who want to go?" Later, when he had calmed down, he added, "This is not the work of a sadhu, this is the work of politicians. You should keep aloof from it."

A sadhu came to Kainchi one noon, when Maharaj ji was resting in his room. He wanted Maharaj ji informed that he had come. The boys who were there said, "We shall ask Dada."

I said, "No, no. If Maharaj ji is to come out, he will come out on his own. We can go and bring him only at four in the afternoon."

The sadhu said something rather harsh, the boys got furious, and hot words were exchanged. While this was going on, Maharaj ji came out. Maharaj ji put a hand on the sadhu, "You have become a sadhu? You failed your school examinations, you stole the ornaments from your family's house, and you ran away. After that you went to Germany and became a very learned person. When you were not able to get suitable employment, you left. That is how you have become a sadhu. I know your father, I know your family. Now you come here quarreling?"

The sadhu was given prasad, but he only wanted to escape. After he had gone, Maharaj ji said, "Dada, you should rebuke the boys. They must not quarrel. They should have regard for the clothes the sadhu wears. They cannot recognise a true sadhu, so it is better they show respect."

Many persons have asked me how it was that Babaji frequently said that kamini and kanchan [women and gold] were the deadliest enemies and yet he was in the company of so many women, even in the ashrams and while traveling.

When Babaji traveled to Madras in 1973, he stayed in the Sindhi dharmashala. While he was there, Hukemchand was told by one of his friends that a great saint had come. Hukemchand was a lover of saints and so went to the dharmashala. There he found a sadhu sitting on the upper floor giving a discourse, surrounded by many persons. Hukemchand left not very impressed. When his friend asked if he had met the saint, Hukemchand said, "Of course, I saw that sadhu on the upper floor. He was not much to bother about."

The friend said, "No, no. That is not the saint. He is on the ground floor near the staircase."

So Hukemchand returned. There he found a fat old man sitting on a cot, but there was no indication that he was a saint or sadhu. The door to the next room was open and there were ladies talking and attending to him from there. The sight was obnoxious to Hukemchand—that a saint or sadhu was in the company of women and taking their services. He started to leave, but then suddenly turned back and fell at the feet of that person.

Now what charm was applied by Baba so as to convert a more than middle-aged, intelligent and sensible man? Somehow he realised that Babaji could be in the company of any number of women and not be harmed. Hukemchand became a very great devotee.

Babaji was surrounded in Kainchi by so many women. He gave them his ashirbad and let them rub his legs as did any male devotee. But he called all older women "Ma" and all younger ones "Baita" [daughter]. When Radha came with Ram Dass and other westerners, Maharaj ji got down from his cot, bowed to her, touched her feet, and said, "Dada, she is my mother. You also bow at her feet."

Now was it just for show, or was it genuine feeling coming from his heart? When all these persons were sitting around him, Indian and foreigners, men and women, young and old, his sight was not obstructed by the outer vestures of the body or the mind—he saw beyond to the soul.