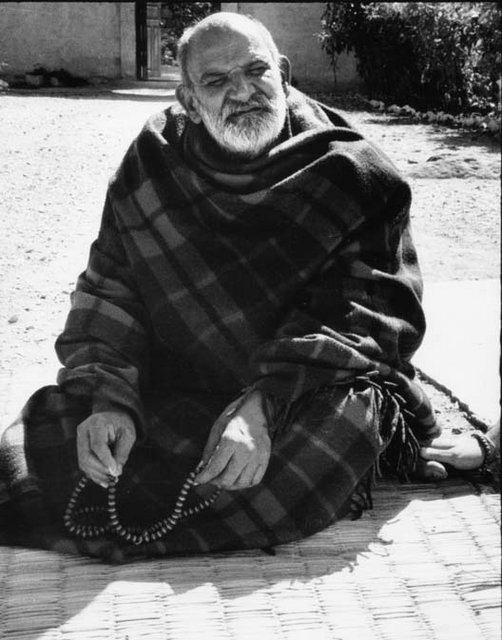

Tularam

Many persons have felt that Babaji's methods of making and remaking the lives of his devotees were often very hard and sometimes appeared to lack mercy.

Many persons have felt that Babaji's methods of making and remaking the lives of his devotees were often very hard and sometimes appeared to lack mercy.

This, of course, was not true. The whole basis of his work was nothing but mercy—kripa for the helpless and forsaken one. He knows where, when, and how much mercy is to be used in the job.

A murti may be made from clay, wood or stone. The work of the clay modeler is done with soft and delicate touches of his hand. When it comes to the sculptor working with stone, he has to take up the chisel and hammer. They are both merciful in their jobs, but the mercy has to work in different ways.

Babaji knew this very well; we can see it in his work at different places and with different materials.

Emptying and cleaning are considered essential in the making of a vessel suitable for holding sacred water. The processes differ from one another according to the state of the vessel.

One might be comparatively clean and soft and simple methods will be enough. Hard treatment is necessary when the vessel has been used for well or pond water and sediments had been deposited; impurities had turned into crusts and clots. The impurities have to be taken out to make the vessel worthy of the sacred water. The task is not simple. Babaji knew it and did it with full consciousness. The cost for the unavoidable surgical operation had to be paid in pain.

In Babaji's method of dealing with us, there is no partiality or favoritism for anyone. The beads in the rosary differ from one another in their size, shape, and color, but the same unseen string passes through them all. Can we accuse the string of partiality because one bead has come first, another in the middle, and a third one in the end?

We have mentioned before that whatever claim we might make of having known Baba through our personal experience does not come to much. In spite of my close association with Babaji, my personal experience counts for little. I have acquired my devotion for Baba and whatever understanding of him I might have from the gifts of the open hearts of his old and selfless devotees.

After shifting to the new house in 1958, many of these devotees started visiting him here during what became known as Baba's "winter camp." Large numbers of devotees began spending their time with him. The house became a hive with bees swarming around him. This was actually Baba's precious gift to his devotees. There had not been any place where he would stay long enough to enable them to have his darshan. There was not Kaichi or Vrindavan at that time to provide that opportunity. The devotees were new to us, but they were well known to each other and close to Baba. They constituted the first batch of the accredited ones, well known for their devotion and dedication to their master, soaked and saturated in their love of Baba—from whom I had my first lessons and from whom I gathered my love and devotion for Baba. There was no question of their being closed or miserly with you, and I took the full advantage of their generosity and open-heartedness.

Bhai (Brother) Tularam and Jivan both came from Nainital and were originally opposed to any association with Babaji, who had been visiting Nainital for many years and was very popular with most of the residents there. Many of their relations did their utmost to take them to Baba and failed. They stayed away from him until the final moment when their conversions came. They were both fortunate to be chosen as Babaji's travel companions, although separately, for journeys to different places. Babaji had been a traveler all through his life and even the ashrams built in the later days could not hold him. He accepted what had been said about the life of a saint. It is all a journey—a journey of the alone to the alone.

Tularam's conversion came in the last few years of his life, but the whole of that time was spent traveling with Babaji. This was a rare privilege not given to anyone else. Actually, Babaji had no travel companion as such. Sometimes he would pick up someone from the roadside inn, as it were, travel with him for some distance and drop him at the next inn. This was his practice, and anyone who was chosen just once felt happy; others envied his luck. So we can imagine the fortunes of Tularam when he served for so many years as Babaji's travel companion across the whole length and breadth of the country.

He visited all the centers of pilgrimage, the temples and monasteries, and met the sadhus residing there. A task which a pilgrim cannot accomplish during his whole life was done by Tularam in a short time at the end of his life. When we talked—and we talked in plenty, undeterred by anything—he would not talk about the temples or the places, but only about his life with Baba. He had gathered much and had filled up his heart to the full. Rather it was over-full. Taking me to be a near one, he was ready to give me the taste of what he was carrying, emphasising all the time that these are the real things and I must taste them fully. I did this whenever we were together. When we parted for good, he left my luggage full, assuring me that when alone or lonely I could take something out of my bag and relish it. This I do even now. It is all fresh for me.

When Tularam joined the ranks of Babaji's disciples, he had already lived through the first two stages of life, student and householder, and technically he was qualified for the third stage, life in the forest, which nobody follows now. One day when someone asked about his family, Tularam said that he had left them behind—the time for that was over when Babaji had come to take him on his travels.

After finishing his education, Tularam began his career as a lawyer. Living the family life with a handsome income, he augmented it by starting a business. When the business was established and the income stabilized, he stopped his legal practice and began enjoying life and living more liberally. He belonged to a well-known family with many friends and relations over the entire region. His son attended to the business, leaving him free; with an assured income, he had not much to worry about. That was the story of his life as he learned it from him, but according to his friends, his coming to Babaji was overdue and was delayed only because he was short-sighted and unreasonable. However, Tularam believed that he did not come to Babaji early in life or through pressure from others because the time was not ripe for him, and I think he was right. Siddhi Didi, his wife, had been with Babaji for a long time and was recognized as one of the topmost of Baba's devotees, so there was no difficulty in him taking his place among the devotees. The delay was because the choice of time was not in his hands.

Tularam and I had come to know about each other after Babaji started coming to our first house, but we met only in the winter of 1959, after we had settled fully in Babaji's new house. Tularam, with Siddhi and others, came in the last month of '59. It was the time of the Ardha (six year) Kumbha mela. Tularam's family was living in a separate house, but both he and Siddhi and the others would say to Baba that he (Baba) could send Siddhi and the others away but he would stay. However, both he and Siddhi continued staying with him. Many other devotees had come to stay, each one happy to be with Baba in the company of his long-time devotees. The whole period of his stay came to be one of continuous celebration, the likes of which we had never seen or participated in before. This was the first winter camp that continued annually, uninterrupted, until 1972.

Besides the time spent with Babaji, we had also enough time to be with each other. Our most enjoyable meeting was at night, and it came to be like a ritual for us. After everybody had finished with work and Babaji was resting in his room, we had our best time in satsang, sharing the most blissful events in our lives with each other, freely telling and retelling our day's experiences. What we had collected indiviually had already been tested and sifted in small groups, so it could be served with confidence. Everyone was keen to see that nothing spurious or counterfeit was allowed to pass in the name of Baba. The light of experience that others earned enriched our own experience.

These nightly meetings came to be very significant for us. They were workshops for learning how to enjoy life in the company of others drawn from far and near, knit all together into a happy family. These were the proudest moments in our lives. We were all included in Babaji's family and were entitled to have our share in everything. Everyone became each other's own dear ones, together only to help each other enjoy their share. It had previously been the lot of all to experience the suffering of typical petty family life, full of fear and jealousy; now it was amazing and unbelievable that the family life could be so very happy and blissful. The great lesson we learned was that happiness would come only if we learned not to shut anyone out as a stranger, or deny anyone his share and place in the family. Happiness comes through the path of oneness—oneness with whomever you are brought in contact. From whom can there be fear, for whom can there be jealousy and hatred when there is only the One with you and none else? All are in the One.

This was, no doubt, a precious lesson—the crest jewel of a happy family life, but few of us could learn it completely. It was all right for the time we were with him, remembered and practiced in his presence, but when he went away from us we left it behind. When he was not there, why should one bind oneself? This precious lesson Babaji forgot to give us. We were wise enough to learn it later.

Sometimes during our nightly satsang, Babaji used to visit us in our room, where we were busy with our talk. One night, more than an hour had passed and we were still talking when Babaji entered the hall, sat down on Shukla's bed and began counting the layers of bedding. Babaji said, "You are enjoying much luxury here."

Everyone laughed at the joke, but Shukla was much moved and said with tears in his eyes, "This is my Didi's house, so I have got them."

Babaji said, "Your Didi is good, but she is generous to you and gives you five layers for your bed, but only three layers for mine." Our satsang was punctuated with many such visits and inimitable comments. Everybody would say after such an experience that this really was our Babaji, the one whom we all seek.

Days passed in quiet succession. All we wanted was that the ecstasy and excitement in which we were spending our days should not halt. But one night, after Babaji had gone to bed, the devotees finished their meals and assembled in the hall as usual. After some time, we noticed that there was no light in Babaji's room. Taking him to be asleep and thinking we would have no visit from him that night, we all took to our beds. Before twelve, everyone was asleep and all the lights were switched off.

We were all in deep sleep when we heard Tularam shouting, "Dada, Babaji has gone away. He is not here in the house." Tularam caught me by the hand and started running for the gate. Siddhi was already there waiting for us. We had not even taken our slippers when we started running on the road. We came across a rickshaw by the roadside, but the rickshaw-puller was asleep on it. Tularam actually pulled him down. We took our seats and Siddhi jumped on the footboard and asked the rickshaw-puller to drive fast. He was not fully awake, and that there was no accident was only because there was no traffic on the road.

When we arrived at the railroad station, we saw Babaji sitting alone on a bench. The two devotees who had come with him had been sent for their tea, so Babaji was alone when we came before him. We were agitated and could not talk, so he started the talk in a very casual way. It was as if he was sitting on his bed, where we had left him earlier. He inquired how we came to be there. Tularam replied as Siddhi and I could not talk or even open our mouths, "We came in search of you. How was it possible for us to stay at home when we learned that you had gone away?"

Babaji behaved as if it was a very common and everyday affair and we had unnecessarily given so much importance to it. Then the usual questions began, as if cursorily directed to Tularam: how did he know, what did others think when they heard of it, and all such questions. Tularam could tell him only the little which he had heard from Siddhi when she came rushing down to wake us up.

Everybody had been sleeping in the house, but Siddhi and two other ladies who slept on the roof above, were sitting looking toward the road in front of the house. It was a full moon night, and they were sitting silently, as if in meditation, when they saw some movement going on there. Two rickshaws had come and were standing at the gate when someone came out carrying something in his arms. The gate was opened, and there were some others waiting there. They all sat on the rickshaws and started off. The ladies saw but did not understand what it was all about. The eyes had given all the snapshots to the mind, but it could not develop them immediately. What all the pantomime was about, they could not know.

Babaji said that the thing was so simple that it was a surprise for him that we could not understand it. He said that he had some important work at Mathura and his presence was necessary there. Moreover, Ram Prakash, who had come from Agra, was wasting his time here and his work was suffering, so he had to be taken home. He continued, "This was decided at night when I was going to bed. You were busy with your food. Kanhai Lal came to see me before leaving for home. I asked him to come with two rickshaws after two in the morning. I could not ask you because you were all busy with your food. When the rickshaws came, I was ready to start but you were all asleep. So I came out of my room alone and when I saw Ram Prakash sleeping on the verandah along with others, I lifted him and took him out of the gate. My problem was that he should not know it. If he woke up, he was sure to draw everyone from the house by his shouting. So the wise thing was not to wake him. For such a simple thing there was no sense in making a fuss like you people would have done. One must use one's brain before anything. You people do not do that. That is the cause of all your trouble."

The sermon was over. Then as consolation for our troubles, he said that his work was very urgent. It had not been in his plan to go now, so he did not talk to us about it. However, he would return soon. Ram Prakash and Kanhai Lal had returned and were standing nearby. It was almost time for the train to come, so Babaji said we should return home. It was then that Tularam asked him the question which had been itching at his mind for so long. He said his only request to Baba was that henceforth he should not leave the home without telling Dada about it; it was painful for Dada when he learned that Babaji had gone while he was sleeping. Babaji smiled, and granted his prayer outright, "All right, from now on I will let Dada know before leaving the house." A promise, very precious, extracted by Tularam for the benefit of us all. Babaji honored his promise till the last day before taking his samadhi. Whenever Babaji informed me that he was leaving the house, I was reminded of Tularam and his love for me.

Babaji returned after five or six days. Many devotees had left for their homes, so Tularam and I had plenty of time to talk. He had much to say about Baba. He had spent many sleepless nights sitting or moving with Babaji in Nainital, Almora, Bhowali and Bhimtal. It was a life spent on the streets, sometimes inside a culvert on the roadside. for those who spend their lives in furnished houses and soft beds, it was a tough life and often painful. But no one would think of giving it up. They were caught like bees in honey, but not in the hive anymore.

Meals were uncertain, but no starvation loomed for anyone. There would be some roadside shops with open doors. When the doors were bolted and the people within were sleeping, you could wake them up and make your purchase. When they were near some village or house, some would go to collect food, whatever it might be. There was no question of the food being good, fresh, stale, sweet, or bitter. It was food to satisfy your hunger, and when you are so very hungry, any food tastes very sweet. Seeing Babaji, who was well known in these areas, many householders would bring food and delicacies for him. Sometimes devotees provided a full-scale picnic on the open road in the middle of the night, the joy of which could never come from eating alone in one's own house. Sometimes tea would be brought or someone would prepare it by kindling fire near the road and collecting the ingredients from the houses or shops in the area.

If there was a problem getting betal or cigarettes for Tularam, someone like Jivan would collect them from wherever they were available. Sometimes, when food was late in coming, Babaji would send Jivan to purchase all the betals in the shop, so that Tularam could chew them. Was it not a miracle that a person accustomed to a life of eating rich and delicious food, accompanied with sauces and sips, could now satisfy his hunger by chewing a bunch of betal nuts? Tularam used to say it was a miracle that he—a lawyer and the owner of the India Hotel at Nainital—was now moving over thorns and stone chips and satisfying his hunger with whatever was given to him before the eyes of his master.

From the time we came to know and love each other and open our hearts, Tularam named me 'Udhav,' the servant of Krishna. He said one day very excitedly, "Udhav, now I can see it. It is all sheer grace to train and equip me for my vanprastha—my life in the forest." There was no question of arguing with him. Agreeing in full was all that was left for me. Sitting with him, hearing him undisturbed, was a rare treat seldom available in the crowded house. Moreover, these sittings were always associated with gulping tea and smoking. When Babaji was in the house there was no opportunity for undisturbed sittings.

Tularam was a pukka convert by now. Out of his love for me, he tried to draw me out, to float in the mainstream with him. "You come to be dear to you," was his motto regarding me. He was a shrewd lawyer and knew how to plead a case. I was not gullible enough to make his job easy, but I was pliable, and that helped him in his task. Relying on his own experience, with untiring efforts and infinite patience, he aimed to raise me to the rank of Babaji's devotee. Whatever little I have attained and for which I am admired is mostly due to his unceasing labor of love. Others might not know this, but it is always in my mind.

After Babaji returned, our nightly sittings resumed as before. One morning Babaji left for Benares by car along with Tularam, Siddhi, and a couple of others. In spite of all efforts of Tularam to take me in the party, I was left behind. Babaji's reply to Tularam was, "There is so much work for him in the house. How could he accompany you?" After a couple of years this came as a clear and distinct order that I was to stay at home, as my work was there.

After they all had left that day, a colleague from the university came and told me that his guru, Shri Deoria Baba, was coming in the evening to bless him in his newly-built house. He asked my help with the arrangements in the house and with the reception of his guru. I could not agree to it, telling him Babaji would be returning by evening, and with him in the house, I could not move about. Moreover, there was not any interest in my mind to meet his guru. He insited, saying his function would end before Babaji returned, so there would not be any difficulty. I went under pressure, not as a choice of my own. After restlessly waiting a long time for his arrival, Deoria Baba came in a big open car in the company of many sadhus, his disciples. There was a big crowd waiting for the darshan of the great Mahatma. After he was seated, I escaped stealthily without informing my friend or anyone else.

Later that evening, Babaji returned and spent some time with the visitors waiting for him in the hall. He said that he had to return knowing they would all be thinking of him. After a brief talk about his visit to Benares, he asked for prasad to be given to them and then sent the visitors away. When everyone was gone, he asked my mother to give him food, as he was hungry. After he had taken his food in his room with me, Maushi Ma, and Siddhi, he sent them away, asking them to feed everyone staying in the house. We had no sitting at night, as Babaji said everyone was tired and must all retire now.

The next morning we gathered round Babaji, as had come to be our practice. He was on his big cot with Tularam, Siddhi, and Maushi Ma sitting before him. I was standing by his cot. He was talking to those sitting before him, and then turned to me and asked abruptly, "Did you meet Deoria Baba?" I was taken by surprise, as this all happened in his absence and no one had talked to him about it. He began talking about Deoria Baba—a great saint, having many disciples. "The sadhus and many other devotees must have come with him to your friend's house."

What reply was I to give? Then he resumed talking, "When they were late in coming you were thinking of running away." Everyone was all attention. Then he asked, "Did you talk to Deoria Baba? Did you talk, or not?" After his repeated question, I said I did not do that. "Why not, why not?"

What could I say? Something came out of my mouth, which I had not thought consciously. "There was a big crowd, so I could not get my chance," was the reply I gave.

Immediately he retorted, as if jumping on me, "You should have taken my name. You should have mentioned my name. Why did you not do that?" When no reply was forthcoming to his continued questioning, he caught me by the hair, and pulling softly went on, "Tell me, tell."

My reply came, as if pulled out by some force, "For me, one Baba is enough."

I did not understand what I had said, but Tularam shouted, "Oh! Oh!" seeing me standing dumb, nervous before everyone, Babaji took mercy on me and started patting me on the head, not longer pulling my hair, as if to help me get back my lost confidence. He was repeating, "Thik hai. Thik hai." (It's all right. It's all right.) The silence continued for some time with only Baba talking and everyone's ears keyed to hear him. Many more persons started coming in, and he changed his topic and talked about things of interest to all.

When we met that day in our free moments, Tularam congratulated me, saying, "You've been given the most precious thing of life, not given to anyone else." When I said I was not aware of what he was talking about, his reply was that I need not be, that I had it, and it would work of its own. It was long years afterwards that I understood what Tularam had meant and for what he had congratulated me. realization comes at its own time, and not of our choice.

Another day, when I entered the hall in the morning, Tularam and Siddhi were already there sitting before his cot. Tularam had a thick book, Ramacharitmanas, in his hand, which he had been asked to read. Seeing me, he handed over the book asking me, "Udhav, tell me, wherefrom should I read?" I said I had not read the book or any other version of Ramayana. Tularam might not have believed, but Babaji spoke out, "Where is the need for you to study it?" But Tularam was relentless, and handing over the book again, asked me to open to any of its pages. I did it and the open page came to be in Sundar Kand. Tularam said, "What now? This is what to be read." I looked at Babaji in amazement. Unknown to anyone else there, there was another incident like this, in this very hall, of which Tularam talked much. But that came much afterwards.

It was in March that Tularam left with Babaji. The satsang continued for some time more, but it was just a routine affair. It lacked the zest and thrill of sitting with Tularam either in a large company or with him alone. This was a very memorable stage in my journey—actually the first stage in what was awaiting me. I was to travel on a path unknown to me, and all alone. But Tularam had himself covered a good part of his journey through uncharted lands, and had collected valuable knowledge which would help and guide me. His talks were a travelogue for my own journey. That might be the main reason for my interest in his talks, entertainment aside, they were much enlightening for me. As Tularam used to say, this was actually Babaji's way of preparing and equipping me for my journey, so after they had left, there was much to work out and enjoy. There were crumbs that you could just pick up and put in your mouth. But it was the first lesson, the untying of knots which helped me much afterwards, when tightly bound packages had to be handled.

Tularam was writing regularly, giving an account of what was going on in his life with Babaji. They had gone to Badrinath with Babaji and a few other devotees. The places and the temples visited were minor compared to the meetings with the sadhus and the way Babaji was received and treated by them. Tularam was fully convinced by the sadhus' talk that Babaji was the 'greatest sage of the age,' as he started calling him. This was further confirmed by the sadhus at Dwarka, Rameshwaram, and Jagannath Puri when he visited them with Babaji in 1962.

They visited many places during this pilgrimage, but the accounts were given after they came for the winter stay in November. It was known that Tularam would complete his pilgrimage to the west, south, and east early next year and would start from here. It was somewhere in the back of his mind that he would persuade Baba to include me in his party. When he mentioned it to me, I said there was no such hope as I was pinned down here in the house. I did not know how I had a premonition of it, but it subsequently proved to be correct.

This time when Babaji arrived for his winter stay, the devotees started assembling in large numbers. They were old devotees, but some of them were new to me. Tularam had talked to many in the hills about his experiences the winter before, and that had attracted many new ones. In a short time the satsang was in full swing, everyone participating, with Babaji or without him. Soon there ceased to be any distinction between new or old, rich or poor, educated or uneducated. All differences ceased to exist within the real fusion of hearts—the miracle of the 'Great Fusion'—of which I was a witness. While many of us were fearful that the satsang might end soon due to the impending departure of Babaji for the west, Tularam informed us that this journey had been shifted to winter 1962. Instead, short visits to neighboring towns or pilgrim centers were started, the most important of which was Chitrakut.

At Chitrakut for the first time in 1961, Tularam was going around Kamadgiri with Babaji when he saw that 'Ram Ram' was written on the leaves of the trees. When he pointed this out to Babaji and asked how it could happen, Babaji's reply was that there was nothing unusual about it; this was the land of Ram, and not of any human being. You have your name board in front of your house, and if Ram's name appeared on the leaves, it was all quite ordinary. Tularam told me when we were sitting together in Allahabad that Babaji's logic and argument were so perfect that he felt like pitying himself for his ignorance in asking the question. With this there was only laughter left for us. How simple things would be if only we could believe in them.

The satsang spent almost all its time staying home and talking to each other. They had plenty to enjoy, and nothing to seek from anyone else so long as they were in the shadow of Baba. Tularam left in March along with Baba, and others left separately for their respective places. Tularam continued writing at least once a week. He would give a picture of his excursions, and the new faces and places visited, although the guide and guardian with him on his journey was always the same.

After they had all gone, the sensations of festivity and celebration came to a sudden halt, but there was no vacuum in my life or any problem of idle time. During the time with the devotees during the winter months I had cut down my routine duties here and there. The duty in the lecture rooms was fixed only for a few specified hours, but responsibility for the students could not be confined to the classroom. It was a time-consuming affair and did not leave time to think of other things. Many things would take hold of me, helping me forget the loss of my friend. It was like the special fund built up for celebrations and festivals, collected by cutting down the routine expenditures of the household. However, like all celebrations, when they came they were celebrated to the full at whatever cost, and when they ended, they left behind a trail of joy and happiness through association with his devotees, whether they were present or far away. When Babaji has drawn you to him, everything is given to you in his own shadow. One must learn this and drive away worries from the mind.

A striking thing occurred, the first of its kind for us, in September of 1961. One morning I discovered "Ram" written on the book in Babaji's own hand, when he had not been here for the past several months. This was unique, and I wrote to Tularam who was with Babaji at that time in Agra. Babaji said that Dada was remembering him, so he had written "Ram" on the book as proof of his visit.

It was winter again when they all returned, and soon life returned to a high pitch. Whether it was a chorus or a symphony there was a role for everyone, and rewards in plenty were available to all. Living like this one could learn that life was not only misery and drudgery, which we had known for so long, but it was also full of peace and joy. This secret is disclosed to us only when we are drawn to the saints. This is the task with which the saints are busy—giving us a taste of the real beatitude of life and throwing light on the path leading to it. Tularam had taken a taste of it and wanted it for me also, but I had not yet become an accredited or qualified recipient, so his efforts went into preparing me for it.

Babaji and Tularam left for their pilgrimage in early '62 and spent several weeks going from one place to another. Tularam always sent reports of the tour, but it was only after their return that we had details. When they had reached Dwarka, the head priest of the temple welcomed Babaji and introduced him to everyone. He said that Baba always lived in the temple and narrated a lot of things about him. There was also an old Hanuman temple there associated with Babaji's name. Babaji admitted that a part of his earlier life had been spent in that area.

The most striking thing for Tularam during the whole tour was the way the whole journey was one of homecoming, meeting old and intimate associates who were jubilant at Babaji's arrival. He repeated again and again that Babaji was known to all the sadhus and heads of the ashrams and temples they visited. Babaji followed no rules or rituals in these sacred places, but he made them go through each one as the custom of the place demanded. Babaji seldom entered any temple for darshan, but gave his appropriate respects by folding his hands and allowing the sprinkling of sacred water on his head. The others—the darshanarthis (pilgrims seeking to be in God's presence)—were directed to go into every temple. With Babaji as your guide, there were no problems with entry into the temples or sacred places which were not easily available to all.

Tularam remarked that the real pilgrimage was to be with Baba; visiting places and temples was of lesser importance. It had been the wish from an earlier stage of his transformation to visit the four sacred places of the HIndus. He had not yet been close enough to Baba to know that all pilgrimages were in him.

After their return from the pilgrimage, there was not much time until the end of winter camp. Having collected much through his long and memorable journey, Tularam was anxious to share it with me. Every minute that we could steal from the hectic life would be utilized in retelling his experiences to me. The enthusiasm and excitement with which they were related was not expected from a man of his age or upbringing, but everything was possible when you were under the spell of intoxication. It was mostly at night that we used to have our time together.

One day, while everyone was busy with the day's work, Babaji went out with some of the devotees, including Tularam, to the bank of the Ganges. After spending the whole day there, they returned in the evening when the hall was full of people waiting for his darshan. While entering through the gate, he started shouting and upbraiding me: "You are such a badmash (rascal) that you have kept everyone hungry in the house. I am also very hungry so bring my food." Everyone was stunned by this outburst of temper, but I would not obey. He wanted to have his food in the hall in front of everyone, which was not his usual practice. He used to take his food in his own room with the mothers around. He would always remind everyone, food and prayers were to be done by sitting in a corner. So I did not bring his food into the hall at first, but was forced to do so after repeated haggling. When a few chapatis with vegetables were brought on a plate, he took them and started throwing them to the people sitting in the hall. I brought one bunch after another from the kitchen. The pan in which Didi had kept her chapatis could hardly accommodate thirty pieces, but more than one hundred pieces were distributed from it and still it remained full!

After some time when everyone was busy hearing his talks, he stood up and catching hold of my hand, came out to go to the urinal. Moving slowly and speaking to me in an entirely different tone, he said that it was not right for me to keep everyone hungry in the house. He had been on the bank of the Ganges and was enjoying his time sitting there. He could not take his food because we were not taking our food in the house. If I had taken my food, then Ma, Maushi Ma, and Kamala also could have taken their food with me. I had kept everyone hungry, including him. In the afternoon, the guests staying in the house were fed as usual, but we could not eat, as Babaji himself had not eaten. The next morning he left again, appealing to me that if he were late in his return, I should not keep anyone hungry in the house.

This was the day that the drama enacted on the bank of the Ganges culminated in his recitation of the immortal mantra, "Everything is accomplished by taking the name of Ram." The major part of the drama was played out in the presence of all with him—Tularam, Siddhi, Shukla, Girish, and Didi—but the climax and culmination were only for me. This was the most memorable day in the lives of the devotees, in the opinion of everyone. And so it was.

One morning, Babaji began talking about pujas and prayers and going on pilgrimages. "Prayer and worship should be done by everyone, every day, as the highest obligatory duty to God; visiting temples and pilgrimages should be undertaken only under favorable conditions and suitable times. They are not essential for your worship and religious duties, whereas prayers and pujas are, and must be done in some form or other." When everyone was hearing him with full attention, he looked at me and said curiously, "Dada, you stay at home." I did not understand what he meant by that, so I could only reply simply, "Thik hai, Baba." (All right, Baba.)

While we were sitting that night and talking, Tularam said that what Babaji said was not random, but had something to do with my sadhana, my spiritual endeavor. Staying at home meant avoiding pilgrimages to temples and religious centers. He said that they were not necessary for us, since we had secured shelter at Babaji's feet; there was nothing rare or extraordinary we could get from pilgrimages that we could not get by staying with him.

However, most of the time in pilgrimage was spent in Babaji's company, and that would not be possible for me if I were staying at home. Tularam had become so intoxicated in his love and devotion to Baba that there was no sense in trying to place before him my own differences and disagreements with his judgment. My silence was taken by him to be full concurrence with his opinion.

Two days later, our morning sitting with Babaji was interrupted by the visit of an old devotee. He wanted to say something in the presence of all of us, but Babaji prevented this, and took him alone to his room. After some time, Babaji asked me to give him prasad and arrange for a rickshaw. While I was going with him to the rickshaw, the man said he was from Madhya Pradesh. When he was young and working under a forest contractor, he had known Baba. Many miracles happened there at that time. He had been cut off from Babaji for all these years until some people said Babaji visited this place in winter, so he had come in search of him. He had wanted to talk before us all, but Babaji took him to his room and told him that he should not talk about those things. Babaji said that when people who had known him for so many years did not believe these legendary miracles, how could these people believe? It would be better if he did not talk at all.

We had been standing before the rickshaw talking for some time when Babaji shouted for me. He had shifted to the study room and was lying silently on the mat laid on the floor. There were several others with him—Tularam, Siddhi, Girish, And a few more of the house. Babaji asked Tularam to hand over his packet of cigarettes to a young man standing nearby. When that had been done, he said smoking was kharabhar (bad); Tularam must not smoke anymore. He asked the boy to destroy the cigarettes and throw them in the nearby basket. Then he pointed to Ram Prakash to bring his packet of cigarettes from the pocket of his silk kurta and to throw it in the basket. Then the boy came with my packet of cigarettes. Holding it in his hand, he said that this was Dada's packet and he should destroy that also. Babaji stopped him saying, "Give Dada his cigarettes back. Let Dada smoke."

No one could understand what he meant by allowing me to continue smoking. It was a mystery. Was it because smoking was not harmful for me? We were all left guessing. But when I was sitting with Tularam he said, "Did you understand what he meant? Smoking is not bad for you—at least not now. Babaji knows this, and there must be something deeper behind it." He went on, saying that he knew that smoking was not good for him; everyone in his family also knew it, but they had not been able to stop him. Babaji knew how much we enjoyed our smoke when we were sitting together—it was actually the lubrication in our unceasing talks, and he would not stop that. But now because he (Tularam) was to go away, his smoking could be stopped. It was grace coming all the time, but in different forms. I did not understand him fully then, but after going over it for all these years, now I do.

After a few days Tularam left with Baba and his family returned to Nainital. As with the parting of all the other family members going on, this parting was not striking in any special way. Little did we know that this was going to be the last of the winter camps for Tularam in this house. His next winter camp was to be celebrated somewhere else, unknown to us all. This was also going to be an end of our talks for all time. The parting was painful and the poignancy of it was great because we were to lose our talks that had been made delicious with tea and smoke. His parting request was, "I won't forget to write to you regularly, and you must always reply to my letters promptly." I agreed and replied to his letters as promptly as I could, but my last reply did not reach him. He had to go without it. Siddhi told me that even on the last day he was asking everyone if Dada's letter had come.

After leaving Allahabad, Tularam and Babaji spent time in places near Agra and Mathura meeting old friends. Tularam became ill and was moved to Nainital. All kinds of treatments were started but the condition did not improve. Ultimately, he was shifted to the hospital there. He had so many friends, all of whom visited to console him in the suffering. Babaji visited him also in the hospital and full consolation came from him. He started for his new winter camp with full confidence after Babaji had placed his hand on him in the hospital.

Tularam had done so much for me and left much for me to relish and benefit from. He used to say that his meeting with me came when his own conversion was more or less complete, but I was at my grass-roots stage. I had much growing to do, but he was satisfied that the progress was very rapid. When I tried to compliment him for his achievement, he would return it, saying that he could not claim any credit for it. Everything was done by Baba.

After Tularam had left, my tea and cigarettes continued as more or less a tame affair without any zest or punch in them. Once, Barman, who was an old devotee and close to me, came from Delhi when Baba was here in the winter. He relished his tea and smoke as much as I did, so we took the first opportunity after Babaji had taken to his room. While we were busy in the hall, we heard some laughter coming from Baba's room. When the mothers came out afterwards, they told us how Babaji had described to them our 'tea and smoke ceremony.' He had said, "Dada is with his Bhagwan (God) today." Then he made the gesture of lifting the cup to the mouth with the left hand to show our way of drinking, and with the palm of the right hand open with two fingers close together, he showed our way of smoking. To give a very realiztic touch to our smoking, he drew his fingers near his mouth and made the appropriate movements with his lips. This was the cause of the peals of laughter coming out of his room. While we were busy in the hall with our pleasures, they were not denied their share.

After Barman's visit, there was no one left either here or in Kainchi or Vrindavan with whom I could enjoy my smoke. In Kainchi I was busy all the time and could never go out to collect any cigarettes, but friends were advised to bring cigarettes for Dada. Whether I could smoke or not, they were lit for me when I had moved a little away from him. Of course the cigarettes would be thrown away when Babaji called for me. In Vrindavan, everything was in the open and before Babaji's eyes, so there was no question of making any effort to try and snatch a puff or two. But he never forgot that I enjoyed my smoke.

One day, I was with him for the whole day with no chance of smoking, so he created the situation for me. He was sitting on the verandah with a large number of persons all around. He asked me to take my two minutes off, and with his two closed fingers and the movements of his lips, he indicated my standing and smoking nearby. He pressed me to enjoy my smoke. Everyone burst into laughter, taking this to be a good joke at the cost of Dada. I could not join with them in their laughter. It was too deep and meaningful for me. I had all the joy that no cigarette alone could give, so I did not go for one. I stood before Baba as before, and he understood why I had not moved.

In Kainchi, there was one shop nearby from which my cigarettes came. In 1972 when I reached there, I saw a new shop on wooden legs near the gate on the road. Siddhi narrated how two days back, Babaji had told the shopkeeper that Dada was coming, and he should get a big carton of Scissors cigarettes. This is the Baba I know—providing everything you need after it has been considered whether it's harmful to you in any way.

This consideration of Baba for us reminds me of Ram Thakur, who had the same kind of consideration for his devotees. Once Ram Thakur was traveling by train from Howrah with two of his close devotees, both of whom were great smokers. However, they would not smoke before their guru, so whenever the train stopped at a station, they got down and lit their cigarettes. But before they could take a puff, the train would start moving and they would have to throw away their lighted cigarettes.

When they returned to the train, Thakur said in all earnestness that these botherations of going to the platform, lighting the cigarettes, and then throwing them away unsmoked were not necessary at all. His advise was that being in the train comfortably, they should turn their backs to him, light their cigarettes and enjoy them to the last puff. They were obedient in everything the guru ever wanted them to do, but for the first time in their lives they could not obey. They sat silently bending down their heads. There was no more thought of cigarettes in their mind. All their thoughts were captivated by their guru, the ever vigilant and gracious one.

When we think of these great gurus, unmatched in their wisdom, dedicated to the good of all, untiring in their zeal to enforce the laws of noble living, we wonder how they can sometimes encourage us to do things considered unworthy for disciples. We were taught from childhood the value of sadachar (right conduct) and the rules that were to be strictly obeyed. They include many prohibitions, such as no indecency like smoking and drinking before elders, particularly teachers and preceptors. That being so, how could these gurus tempt their disciples to smoke before them, and thereby throw away the rules of sadachar? Were such rules obligatory or could they be broken at the behest of the master?

I can never forget Tularam's company in enjoying tea and smoke, and I missed that most in parting with him. I had been separated from the friends of my social life with whom I used to enjoy myself in full abandon. But with the coming of Tularam to Babaji's house, this returned in a more appropriate form. Many devotees came, but with so few of them could I smoke and sip tea freely. When one wanted to enjoy the pleasures of the 'tavern' life, one must flock with the habitual tavern visitors. I had that with Tularam and no others. As Tularam used to say, an extension to his smoking was granted simply because our enjoyment could not be cut short. Babaji would be mostly in his room surrounded by the mothers, entertaining them with his pleasant talks and caricature, when Tularam and I would be sitting in the hall with our tea and smoke. Baba would seldom deny the mothers their laughter at our cost. "They are lost in their talks. Both of them are experts in drinking tea and smoking cigarettes. When they talk with a cup in one hand and cigarette in the other, they forget that there is anything else in the world."